And Casey’s Counting ‘Em Down

“A good traveler is one who does not know where he is going to and a perfect traveler does not know where came from. “

–Lin Yutang, Chinese writer.

When the end finally came, it came quickly.

Once I returned to the kibbutz, I learned both Capre and I had been replaced by…. Frederick, the automaton. Where we had struggled to meet rushes, he handled them without breaking a sweat. My fall from grace was complete. Instead of going to the start of the belt where I could fondle melons, I ended up at the back-breaking end of the line where I had to spend all day stacking boxes.

On the plus side, there was mail waiting for me. A package came from Katy Koenen, my most faithful correspondent. Although I rarely heard from most of my friends, even when they knew where I was going to be weeks in advance, there was always a letter from Katy. Australia, Singapore, Hong Kong and Warsaw, there would be something waiting. I was surprised I hadn’t heard anything from her in Israel until I got the package. She had sent it to Tel Aviv, but it arrived after I reached the kibbutz, so the American Express Travel Service Office returned it. When she got my kibbutz address, she expressed it back. I don’t think I’ve ever been so grateful to get new underwear and socks. It was better than all the birthday gifts I’d ever received.

I was so thankful for the first store-bought new clothes I’d seen in months I decided to make her a special gift: a tape of a day in the melon factory. It started with the sounds of melons hitting the waxer and featured interviews with many of the people who worked on the line including melon fondlers, melon measurers (who dropped melons through wood cut-outs just for me), packers and the people who put the boxes on pallets. There was so much tape left there was even room for a duet involving another pallet loader and myself singing “I’ve Been Working on the Railroad.”

The highlight was my interview with Frederick.

“And now, we’ll meet Frederic, who stole my job,” I said into the tape recorder as I climbed to my old home.

“I’m doing a tape on a day at the melon factory for a friend back in the States. Frederic, would you like to say a few words?” I said as I held the recorder to his face.

“Are you crazy, or what?” he said, in a flat, expressionless voice, sounding like Arnold Schwartznegger.

“What,” I replied, without missing a beat.

Although he did it humorlessly, he went along with the gag and put several types of boxes down the chute just so Katy could hear what each size box sounded like going down.

The question of my destination also was resolved upon my return. Thanks to my travel agent, I would get to go to Seattle first because she pulled a fare covered a trip to Seattle, two weeks in Fort Myers, a stop in Albuqerque for my sister’s wedding and a return to Seattle for under a $1,000. The solution meant I would get home in time to vote in the presidential election and start my life again.

I still had a few unfinished details, however.

There was, for example, the small issue of the cow head. During my only solo walk in the desert I found the skull of a cow or other animal and thought it was a great souvenir. The only problem was convincing Israeli postal authorities. So, I went to Eilat, fully prepared to battle, only to have the clerk open the box, shrug, tape it and stamp it. Apparently, she had seen stranger things mailed.

Having not had a haircut since coming to the kibbutz, I also went for a haircut. Leave it to me to find the one barber in town who made a trim an adventure. Apparently, he didn’t understand English, but another man in the shop did, so he translated.

“Do you want a little, medium or a lot of hair taken off?” he asked.

“Medium,” I said, foolishly placing my hair in the hands of a barber in a country of so little moderation that the White House is considered a minimum-security facility.

If my cut was medium, I’d hate to see the maximum. The only way more could have been cut is if he’d left me bald for generations. I had so little hair left that people on the kibbutz didn’t recognize me. A few even came up to my table in the dining room, introduced themselves and asked where I was from. When they realized their mistake most just stared, mouths agape.

Leaving a kibbutz isn’t a big deal unless the person was a long-timer or well liked. There’s an occasional farewell party and then the volunteer takes the long, lonely walk to the end of the driveway a quarter of a mile away, hails a passing bus and rides alone to their next destination. A sort of ignominious reward for months of service.

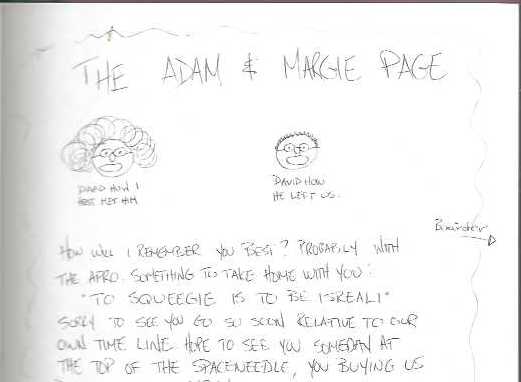

I didn’t face that fate because I cashed in on the trip the kibbutz gave volunteers who had been there for more than six weeks. In this case, it was a group trip to Jerusalem, Masada, Ein Gedi and the Dead Sea. My decision meant I got a muted farewell from the volunteers and members I really liked, without having to get hugs from the people who drove me crazy. I also asked close friends to sign my new journal. The results ranged from the touching to the truly bizarre. Volunteer Margie Sills left me with these words of wisdom; “To squeegee is to be Israeli.” Her boyfriend said, “Never before have I met a man who could tell jokes, juggle melons, play baseball, bad mouth the boss’s son and play New York, New York on the banjo all while singing ‘I’ve Been Working on the Railroad’ in Swedish.” And one of the Swedes left this sentiment: “Hope you get a good life because I’m going to have one of the best lives in the world (or Sweden, anyway”).

When I asked Frederic to sign, his response was short, but simple, “Are you crazy, or what?” He relented and wrote something I’m sure isn’t complimentary in French and finished off with, “Once upon a time, a little kid whose name was David decided to be a very famous reporter, all over the world. For that he was working and working every day harder and harder. But, unfortunately, at the end he finished his life as a “box melon worker” in the very well known Kibbutz Ketura…What a bad and sad story.”

Gee, thanks. As another friend once said, “With friends like these, who needs a stuffed nose?”

It was the perfect farewell: Low key without anyone making a big deal. I’d had a long trip and wanted a quiet departure. Don’t get me wrong. I’m not a shy, retiring guy who fades into the woodwork and avoids the center of attention. I’m a loud, boisterous, funny ham and when I die I want people to throw themselves on my coffin crying, tearing their clothes in grief and falling in the aisles, but death wasn’t imminent, departure was.

The field trip smoothed my transition from the land of melons to the real world. Instead of riding back to Tel Aviv alone, I was in a bus full of people I knew and (mostly) liked. The Swedes constant impressions of Bart and Homer Simpson reminded me of the part of Ketura I would miss. At the same time, Claire’s argument with a charter bus driver over whether or not we should be allowed to have food on the bus long after the issue had been officially settled reminded me of what I wouldn’t miss. And our pistol-packing volunteer coordinator-turned-guide’s tour of Jerusalem gave me a new look at an Old City when he read passages about the holy land from Mark Twain’s “The Innocents Abroad.” Any man who quotes Twain isn’t all bad.

We even stopped at Ein Gedi, again. The difference this time was that we went beyond the second set of waterfalls and into the mountains. This hike was 45 minutes longer than my first, but it was great because the falls further up the trail made the earlier set look like a shower pouring into a swimming hole.

When the group left me behind to catch a bus near the Dead Sea I realized that the longer hike had given me a new take on the country. By delving past noisy soldiers, the endless battles between Arabs and Israelis and the increasingly strident debate about who is a Jew and who isn’t, I was finally able to see a beauty in the land that went beyond the historical and the biblical.

I never had the moving religious experience so many other visitors to Israel talk about, but, then again, I never found out what happened to my relatives, either.

Two days later I boarded a plane for the long trip home happy to be wearing my first new clean, fresh underwear and socks in more than a year.

If Lufthansa Airlines had lowered stairs and let all of the passengers out on the tarmac as they did at some airports I visited, I would have kissed the ground. Unfortunately, the plane hooked up to a Jetway and we walked into an air-conditioned extension of the airport and I wasn’t about to bend over and kiss the carpet. I know it doesn’t make any sense. After all, I’m sure the hallway was vacuumed several times a day and was undoubtedly cleaner than a piece of pavement where thousands of airplane tires have rolled across and gallons of oil and jet fuel spilled, but there you have it. There’s no accounting for taste.

One of the best parts of coming home from a multi-country trip is being able to go to the “citizens only” line at Customs. It moves so much faster.

The reality of my return didn’t really sink in until I bought a Coke at the airport McDonald’s 20 minutes later.

Not wanting to cash a traveler’s cheque, I reached into my money belt and pulled out the old, creased $5 bill that had turned yellow when I spilled medicine in my backpack a century before. It was the same bill money exchange places all over the world rejected because they were sure it was counterfeit.

I had extra cash at the ready just in case the cashier refused to accept it, but I wasn’t about to make a big deal about it.

I shouldn’t have worried, though.

The woman took the bill and stuffed it into the cash drawer without giving it a second look.

Man, it was great to be home.