Sunday On The Parkway With Ho

Surviving the culture shock of Southeast Asia was one thing; Vietnam was another entirely.

Since it had only been open to Americans about a year, I didn’t know what to expect. While I’m too young to have ever subscribed to the Domino Theory (which, I believe, says that if you allow one Domino’s Pizza in your town, many more driving infractions by people trying to meet the half-hour guarantee will follow), knowing all the cruelties Americans heaped upon the Vietnamese made me wonder if I should say where I was from. I could always lie and say, “Canada.” To be fair to veterans, the North Vietnamese were just as cruel, if not more so, but what else could you expect? We were in their neck of the woods, they weren’t in ours.

I didn’t go to debate the merits of the war, however. I went to see the places I’d heard about on the news when I was little: Saigon/Ho Chi Minh City, Hanoi, the Mekong Delta, and Hue. I wanted to go where recent history had been made and see the aftermath, even if it had been 21 years since the war.

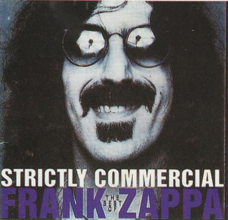

Customs was the first challenge. Since my guidebook told me to declare anything of value or risk having it seized, I reluctantly listed my computer as well as my camera, lenses, short-wave radio, Sony Walkman and tapes. Much to my shock, they didn’t care about my computer, but they wanted to see the tapes. This struck me as odd. I had said I was a writer and had declared that I was bringing a telecommunications device into a Communist country and the powers that be appeared more worried about my corrupting their youth with music. Not wanting to be disobedient, I pulled out all my tapes. I only got as far as my Best of Frank Zappa album. Seeing a tape case cover showing a man with a long beard, shoulder-length hair and cucumbers over his eyes so unnerved the bureaucrat he told me to leave immediately.

My ride to Ho Chi Minh City’s backpacker district was the second most frightening experience of the entire trip. I didn’t even want a ride on the back of the motorbike, I had just gone to the edge of the airport parking lot to catch a taxi on the street (because LP said airport taxis are pricier than those on the street) when a little old man on a rickety motorcycle offered me a ride. Knowing the sheer weight of my pack alone would make it impossible to stay on, I refused, but he persisted. He even took my pack and put it on the bike in front of him to show me I needn’t worry about falling. My next strategy to chase him off was to name an insultingly low price (less than half what he was asking), but even that didn’t work. He simply agreed.

At this point, it’s worth mentioning that there are two important rules of negotiation on the road. The first is that you shouldn’t negotiate for something you don’t plan on buying. I get the impression it’s okay to haggle over something you hope to purchase, then walk away if you can’t get a good enough price, however. The other rule is, if the seller agrees to your price, you are obligated to buy. Not doing so is rude. So I found myself climbing aboard and hanging on for my life as he made a quick U-turn and headed directly into on-coming traffic.

It wasn’t the first time I had ridden with someone who made up his own traffic rules. Most of Indonesia’s bemo drivers do so as a matter of course. Where bemo riding was unnerving, however, this was pee-in-your-pants terrifying because I didn’t have a hunk of metal surrounding me for protection. Hell, I wasn’t even wearing a helmet. I held onto the driver so tightly that if he had made one wrong swerve, I would have seen his life flash before my eyes. At the same time, the white-knuckle adrenaline rush of the ride made it as compelling as a train wreck. I didn’t want to look at what we were about to plow into, but I couldn’t keep from staring in gape-mouthed shock as my driver made his own lanes whilst swimming salmon-like against the on-coming flood of humanity. There were some scrapes so close I had to close my eyes. I can’t prove it, but I’m pretty sure there were times when my driver closed his eyes, pointed the motorbike and hoped for the best.

It was an E-Ticket ride that was better than any roller coaster I’ve ever been on.

Considering that I was within two or three blocks of my lodgings during most of the tour I took of area where I was staying, there’s no reason it should have taken an hour to find my way back, but it did. Never have I seen such a bad map as the one in my Vietnam guidebook. I admit I’m to blame because I took a wrong turn when I left the guesthouse in search of Kim’s Cafe, a popular backpacker hangout, but I wouldn’t have gotten lost if my map had been clear. The lesson I was finally beginning to learn was that the only way to get around on my own was to buy a map of a city before arriving. I never did, but I should have.

I used to think “scooping the loop” was a Midwestern tradition reserved for bored cornbelt kids with nothing to do on a Saturday night. That was before I spent Sunday night in Saigon.

Regardless of whether it’s called scooping the loop, cruising, or driving around, nothing beats the early evening hours of a Sunday evening in Ho Chi Minh City. It’s like the highpoint of an annual festival, Sunday afternoon in the central square of a Latin American city after church and Friday night in a small town after the high school basketball game rolled into one noisy, messy package. Just off Khoi Dan Street, one of central Saigon’s main boulevards, for example, loud music blared from boom boxes on one end of a tiny plaza while vendors sold balloons, small children ran amok, and parents of all ages looked on in amusement at the opposite end of the little park. Meanwhile, on the boulevard 10 feet away hundreds upon thousands of teenagers, young adults, and whole families on motorbikes and bicycles cruised throughout streets filled with the rapidly rising skyscrapers that had quickly sprouted up throughout Southeast Asia in the years before the region’s economic crash. In many cases, the ruins of old buildings that looked like they hadn’t been touched since the end of the war were so close to the latest additions to the street that some corners looked like “Before” and “After” pictures in a promotional brochure for the Ho Chi Minh City Chamber of Commerce. It certainly wasn’t the same as cruising by the Grange Hall on a weekend night.

The whole scene may have seemed normal to a local, but it stunned me to see such odd twists on what I had always considered a middle American institution. For starters, the whole gathering was taking place on Sunday night, an evening when most towns throughout the U.S. are so deserted it would be possible to sit in the middle of downtown without worrying about getting hit.

Just as shocking was the complete absence of cars. There was a logical explanation, of course. Autos are so expensive most people can’t afford them. Instead, most rely on two-wheeled transport. It was in direct contrast with Bangkok, a city where there were so many cars on the road it seemed as if manufacturers were giving them away. What made it even stranger to me is that I had come from a culture where being a young person without a car is an embarrassment. In the States most teenagers would rather stay home on a Saturday night than face the embarrassment of cruising on a bicycle while in Ho Chi Minh City, kids of all ages not only didn’t mind riding motorbikes, many were riding bikes with their whole family. The father would be on the front, the mother holding on to her husband for dear life and the children behind in descending order of size. In many cases the arrangement looked like someone had opened a Russian nesting doll, lined the figures up based on their height and put them on a motorcycle.

Considering the size of the Sunday night crowd, it’s lucky cars are in short supply. The boulevards were so packed with bikes it was a miracle traffic moved at all without any crashes. Putting all those people in cars would invite gridlock so virulent and fatal to a sociable tradition the authorities would still be sorting it out into the middle of the week.

Although I enjoyed the carnival atmosphere, I discovered a downside to the festivities: the difficulty of crossing the street. Local pedestrians seemed cowed and even I, international jaywalker extraordinaire, was afraid to attempt weaving my way through a flood of humanity unregulated by anything as basic as a stop sign. Dodging cars is easy because only a few can fit on a street at any given time, and, no matter how many lanes there are, a pedestrian only has to worry about the trajectory of one vehicle per lane. Facing so many riders making up their own lanes made me feel like a single-celled organism hoping to keep body and soul together while swimming straight across river rapids to get to the opposite shore.

Crossing the street required a leap of faith I wasn’t willing to make. To me, doing so would have been saying, “I am going to keep moving and trust everyone of these thousands of people I’ve never met to swerve around me even though they aren’t required to do so.” It also meant not panicking or stopping in the middle of the stream, even if someone was about to run me down. Stopping short might fatally disrupt the traffic pattern, causing me and everyone nearby bodily harm.

No matter how hard I tried to psych myself up, I couldn’t do it. The drama so entertained local pedestrians they took pictures of me and asked me to pose with their friends. At the same time, a number of motorbike drivers who had watched the drama unfold were highly amused. One finally took pity on me, grabbed my hand and helped me across the street. I asked him if he was an Eagle Scout, but he didn’t speak English, so I don’t know what he said.

I wonder if it’s possible to get a merit badge for this sort of thing.

As I spent the next few days wandering from museum to museum, I noticed the institutions give an interesting perspective on the country’s distant and recent past, occasionally unintentionally.

The War Museum, which, coincidentally, changed its name from the Museum of American and Chinese War Crimes around the time Vietnam and America resumed diplomatic relations, is the perfect example of the unexpected perspective. The name may have changed, but the attitude remains intact. It gives an eloquent look at man’s inhumanity to man using thousands of artifacts detailing America’s (and South Vietnam’s) war atrocities against the Vietcong, and North Vietnamese sympathizers in the south. The wall plaques weren’t always in perfect English, but the displays showing torture methods, unpublicized types of experimental mines and the effects of defoliants needs no translation. In a way, the mangled English is appropriate considering that the building originally housed the U.S. Information Service, an organization that tortured the English language every day, mangling words and inventing new definitions to justify the country’s involvement and prove victory was around the corner.

The museum proves the adage about the victors writing history books. I don’t begrudge the museum’s tone and its characterization of the country being outgunned and overcoming tremendous odds to defeat a corrupt regime supported by an international superpower. The communist party’s success truly is a triumph of the will. Not too surprisingly, the museum never mentions the Vietcong atrocities on American soldiers, however.

Go figure.

The Presidential Palace, now the Museum of Reunification, gave me another glimpse into the period right before the fall when someone else was writing history. Despite all the treasures of Vietnam and other countries on display in the lavish building, the rooms that impressed me the most were the simplest — the President’s underground bedroom and the communications room — because of what they say about the tenor of the times. Located in a reinforced basement far below the first floor, the bedroom is spartan and isn’t much larger than the bare-bones bed where the president retreated on the increasingly frequent occasions when the atmosphere turned ugly and his safety couldn’t be guaranteed.

The communications room and the maps tracing the retreat were just down the corridor from his bed. I can imagine the president walking down the hallway during sleepless nights in search of hope only to find discouragement from the advance of the Communist forces and the ever-shrinking area defended by the South. It can’t have been comfortable, but I imagine the discomfort was nothing next to the misery many Vietnamese must have suffered under the rule of such a corrupt regime. After all, this is the man whose sister uttered the Vietnamese equivalent of a Marie Antoinette-ism after she learned that a monk had doused himself with gasoline and set himself on fire to protest the regime’s policies. I can’t give her exact response because I don’t speak Vietnamese, but I believe it was something to the effect of: “Sounds like a barbecue. Let’s break out the mustard and the ketchup.”

Such nice people.

I also enjoyed visiting the Vietnamese History Museum for what it said about the country’s society today even though it didn’t say it in its displays. At least not so I could tell: all of the plaques were in Vietnamese and there were no translations. The oversight wasn’t too surprising, however, because the institution was designed more for locals than tourists. Other visitors might argue the point but it’s the only way I can explain why the museum also offered brochures in English that didn’t just skip a few odd artifacts, it skipped whole exhibits.

Fortunately, the oversight gave me an unexpected view of daily reality in Saigon I might have otherwise missed. It happened around 11:30 when the employees dropped everything and gathered around a television sitting in the lobby. Noticing the group, I just had to see why so I slowly edged around the lobby to find out what they were watching. Was it a message from the president? Preparations for the upcoming anniversary of Ho Chi Minh’s birthday? The day’s installment of important announcements from the Communist party? The news?

No, none of the above.

Instead, it was “Little House on the Prairie.” I don’t know if I could call it a case of culture shock in reverse, really, but it was unutterably strange to watch a show set in America’s Great Plains, see Michael “Little Joe” Landon’s lips move and hear Vietnamese come out. It was even more surreal than the scene in the movie “Fargo” when an Asian American opens his mouth and speaks with a Minnesota accent. It’s quite disconcerting.

Then there was the Saigon Art Museum, an institution so famous that whenever I stopped people on the street to ask directions they looked at me blankly and all responded with what appeared to be the Vietnamese equivalent of “Say what?” A few residents laughed, some asked if I meant local art galleries, and others insisted it didn’t exist. Once I finally found the place, I realized why. Despite the beautiful French colonial style building that houses them, most of the works were uninspiring. I’m no art critic, but even the oldest pieces, which went back quite a few centuries, were unimpressive.

There was some bad, highly stylized art I did love, however. It came in the form of an exhibit of Vietnamese Communist Party Propaganda posters from the 1980s. I didn’t know how much influence the party had in everyday lives of the country’s people in 1996. I was fascinated to see what behaviors the organization had tried to regulate just 10 years before.

Family life.

Drinking.

Sex.

And the greatest abomination, karaoke.

I couldn’t read the writing on most of the posters, but I was able to piece together that officialdom greatly disapproved. My first hint about the party’s attitude came when I saw a poster showing a man and a woman singing together in a bar on one half of the poster and the same couple reclining and kissing on the other half in front of a sign with the words H.I.V–AIDS SOS. I guess the theory was that singing along to songs in bars causes people to get drunk (or maybe they have to get drunk to sing badly), leading them to lose their inhibitions, having sex and getting AIDS, which, of course, leads to death. In fact, the poster does everything but come out and say in writing, “Karaoke equals death.” No, another poster said that.

It isn’t often I agree with the Communist Party, but this wasn’t just any everyday, ordinary issue. It’s karaoke, it’s evil, evil, evil. And it must be stamped out or it will spread further into the U.S. and more and more people will want to go out, get drunk, embarrass themselves by singing badly in front of others, and then want me to join them for no particular reason because I don’t need booze to sing badly. I can’t even carry a tune in a briefcase when I’m sober — God knows how bad I’d sound if I were drunk. And, of course, karaoke leads to more evils including bad singing in the streets and karaoke addiction, which is even worse because, so far as I know, there is no karaoke wing at the Betty Ford Clinic.

All this is reason enough for me to support the party’s efforts to ban karaoke.

My friends may think this is a contradiction of my long-standing agreement with Voltaire’s view that although I disagree with what you say I will defend to the death your right to say it, but it’s not. While I may defend the rights of others to say what they want, I don’t have to defend their right to sing it.

As I wandered around Saigon, I found myself sidestepping around many small trash piles. The more piles I saw on the sidewalks, the more I thought about the piles I’d seen as I traveled throughout Southeast Asia — huge ones in lots behind losmens in Indonesia, stacks on thousands of construction sites throughout Malaysia, mounds throughout Bangkok–and I was struck by the difference in waste disposal theories between Asia and North America. In America, we pollute a lot in one big place so we won’t have to pollute a little everywhere else, while in Southeast Asia, it seemed they polluted a little everywhere so they didn’t have to pollute a lot in any one location. Whether one strategy is better is subjective and probably depends on where the beholder lives. To most Americans, polluting a lot in one remote place is probably best unless the beholder is poor and unfortunate enough to live near somewhere like Emile, Alabama, where many states send their toxic waste. At the same time, most Vietnamese probably view the other method as appropriate unless they are city dwellers living among all the small stacks.

I was also struck by the impression that Ho Chi Minh City, Bangkok, and many of the other cities I had visited were like America at the dawn of the Industrial Revolution. They are building and making things so fast to try to meet the demand that their infrastructure and laws haven’t kept up. As a result, the streets are dirty, the air is filthy, and the water downright dangerous. But that’s a good sign to local economists. After all, until the 1960s, a sign of economic health in steel towns like Pittsburgh, PA and Cleveland, OH was orange air.

The key difference is that America had time to grow into its Industrial Revolution (even though it was still an environmental disaster) because it was one of the few countries experiencing it at the time and didn’t face any more than the typical types of pressures. Vietnam and other Asian countries haven’t had that luxury. They are in such a rush to keep up they want to get up to speed right this minute in countries that just aren’t prepared for it. Some pretty strange combinations have been resulting: old style garages to repair motorbikes next to shiny Mazda dealerships selling shiny new cars while, down the block, people are still building new roads by hand, using rakes to spread the boiling asphalt mix so that the new cars will be able to drive down shiny new roads. Additionally, new, wider roads were needed in places like Bangkok because 400 new cars were hitting the street every day at the height of the economic boom.

The countries came under additional pressure because they were trying to adapt to technologies that exist elsewhere. America and other first world countries never faced such a shocking, crunching jolt to catch up because they invented the technologies. The second and third tier countries didn’t have that luxury because they didn’t just get to the party fashionably late, they got there after all the chips and dip were finished, the fun guests had left (leaving only the hustlers and low-lifes behind) and the only drink available was bad light beer.