Really Love Your Leeches Want To Shake Your Tree

The most horrifying film to hit the screen,

There’s a homicidal maniac who finds a Cub Scout troop,

And he hacks up two or three in every scene,

Please don’t reveal the secret ending to your friends,

Don’t spoil the big surprise,

You won’t believe your eyes,

When you see..

Nature Trail to Hell in 3-D.”

–Weird Al Yankovic.

I’ve looked at this issue long and hard and don’t get it.

I don’t see what this fascination with trekking in Thailand is all about. I understand the country is beautiful and the hill tribes are interesting, but it seems like everybody goes to Chaing Mai or Chaing Rai to go on a one, two, three, four or five day trek and that every guesthouse offers one or knows someone who does.

I wouldn’t be surprised if sometime soon Chaing Mai authorities make it illegal for non-trekkers to visit. I can see the entry interview now:

LOCAL OFFICIAL: What is the purpose of your visit?

TOURIST: I’d like to wander your streets, shop in your shops, eat in your restaurants and generally spend the bulk of my million-dollar inheritance here.

OFFICIAL: And do you plan to take advantage of any of our fine treks during your stay?

TOURIST: Well, no. To be perfectly honest, I’m not much of a hiker.

OFFICIAL: Very well then, entry denied. (Looking past crestfallen first traveler to next applicant). And you, sir, what are your plans.

TOURIST #2: Committing gawkery with intent to mope, looting, pillaging, murdering, molesting small children and burning villages…

OFFICIAL: And do you plan to do any trekking during your time here?

#2: Of course, you stupid git. How else do you expect me to find villages to burn?

OFFICIAL: Very well, then. Enjoy your stay in Chaing Mai.

This may be an exaggeration, but not by much. Many guesthouse owners ask all new arrivals if they plan to trek before they will even rent a room them. Many want nothing to do with non-hikers because they make their money from the hikes. As a result, the backpacker’s grapevine is filled with stories of guesthouses kicking out non-hikers or raising their room rates. In fact, some backpackers have taken to lying and putting off guesthouse managers just to get a good place to stay.

I don’t know if the Family Trekking Guest House is an exception to the rule because I planned to go on a trek, regardless of where I stayed. The owners weren’t shy about hitting me up as soon as I walked into the courtyard even though it was only 8 a.m. They had me at a distinct disadvantage because I was bleary-eyed after spending the previous day riding from the central part of the country to the Northwest, passing through Bangkok and having to make my way from one end of the city to the other on public transport. I quickly agreed to go on the family’s three-day trek without requiring much convincing or negotiating just so I could get a bed and make up for hours of lost sleep on luxury buses (that feature such lovely accoutrements as stewardesses, pre-packaged meals and video screens that play American action movies, loudly). The only catch was that the next hike wasn’t leaving for another two days.

I’m still not sure why I signed up for a hike. In my family hiking is what you do when you’ve put your car in a distant space during the holiday shopping season and have to walk the length of the parking lot to reach the mall. Still, the trip came recommended, cost only $52 and included a visit to remote hill tribes, an elephant ride and a downriver ride on a home-made raft (although at whose home the rafts were made was never really clear). I figured it would either be a great experience or Thailand’s version of Deliverance.

I might have reconsidered if anyone had mentioned the leeches.

Chiang Mai is Thailand’s second largest city. The air is so much cleaner, the scale is more manageable and the atmosphere is so much mellower than Bangkok. Its compactness doesn’t keep it from being a confusing place to navigate, it just means it takes less time to find yourself again. Although I spent most of my first two hours in Bangkok hopelessly lost and worried I wouldn’t be able to find my hotel, it only took 30 minutes to get my bearings on the back streets of Chiang Mai.

It helps that there are a few more obvious landmarks in Chiang Mai than in Bangkok. There is the moat that surrounds the old city, which was built to provide protection from warring kingdoms in Burma and Laos, and numerous reconstructed sections of the wall that also provided additional security. In fact, I stumbled across so many sections of the wall as I wandered that I spent a great deal of time just staring at maps to make sure I was at the gate or section I thought I was only to find out that I was at a completely different section altogether. Once I avoided that part of town I never got lost again.

The two-hour ride to the trek’s starting point went quite quickly– until we ran out of pavement and had to spin our way around tight uphill turns in the rain. There were a number of places the eight of us (a couple from Wisconsin, two Aussie women, two British college students, a real estate salesman from Malaysia and me) were sure we would have to jump out of the covered jeep and push when the vehicle’s wheels became mired in the mud, but each time our speed-demon driver maneuvered his way out. As the trailhead neared, I started worrying. The rain didn’t bother me, though. Instead, I was worried about keeping up. Although I’d been told the trek wasn’t bad, I had also been warned that the first day was the most difficult.

To be honest, the first part of the hike was much easier than I’d expected. We started by walking downhill until we got to the bottom of a staggered waterfall where the water would drop 10 feet, trickle over a series of rocks on the hillside then plunge another 15 feet. Seen from the bottom, though, the second half of the day’s walk on the other side of the waterfall seemed far more worrisome, since the path veered sharply uphill at a steep right angle. The pouring rain made the footing even more treacherous, but it was nothing compared to the leeches.

The two British students were the first victims. The evil suckers undoubtedly glommed on as we crossed the stream near the waterfall, but that was all it took to panic everyone. The critters were discovered on the lower legs of the two men so early that it was quite easy to pull them off without much damage but by that time, the die was cast. From then on, every 10 steps or so, at least one member of the group would stop briefly and either turn their head and look down at the backs of their legs, lift their legs and check or just repeatedly ask the person behind them to watch and make sure they hadn’t picked up any unwelcome passengers within the last 20 seconds. At each rest stop, one or two of the hikers were stunned to find them on their feet underneath their shoes and socks. The first time I noticed a leech on the back of my leg I was so repulsed that I couldn’t rip it off fast enough even though I didn’t know if it would work. The reaction seemed like such an involuntary reflex that I had already flicked it off with my fingers by the time I stopped to wonder if I could just flick a leech off my leg. It took me five more minutes to realize the leech wasn’t gone, it had merely attached itself to the skin between my thumb and forefinger.

I was so flabbergasted by its reappearance my first reaction was to shake my hand as I would to get rid of a spider that had landed on it. This time, the leechectomy was a success as the bloodsucker went airborne and flew into a nearby tree.

I still laugh when I think what we looked like from above as each of us went through our bizarre self examination rituals while we walked to the hill tribe village at the end of that day’s trail. I’m sure innocent bystanders who watched us would have been hard-pressed to determine if we were a bunch of inexperienced itinerant Whirling Dervish hikers, a dance troupe with apoplexy, or a group of trekkers with Tourette’s Syndrome.

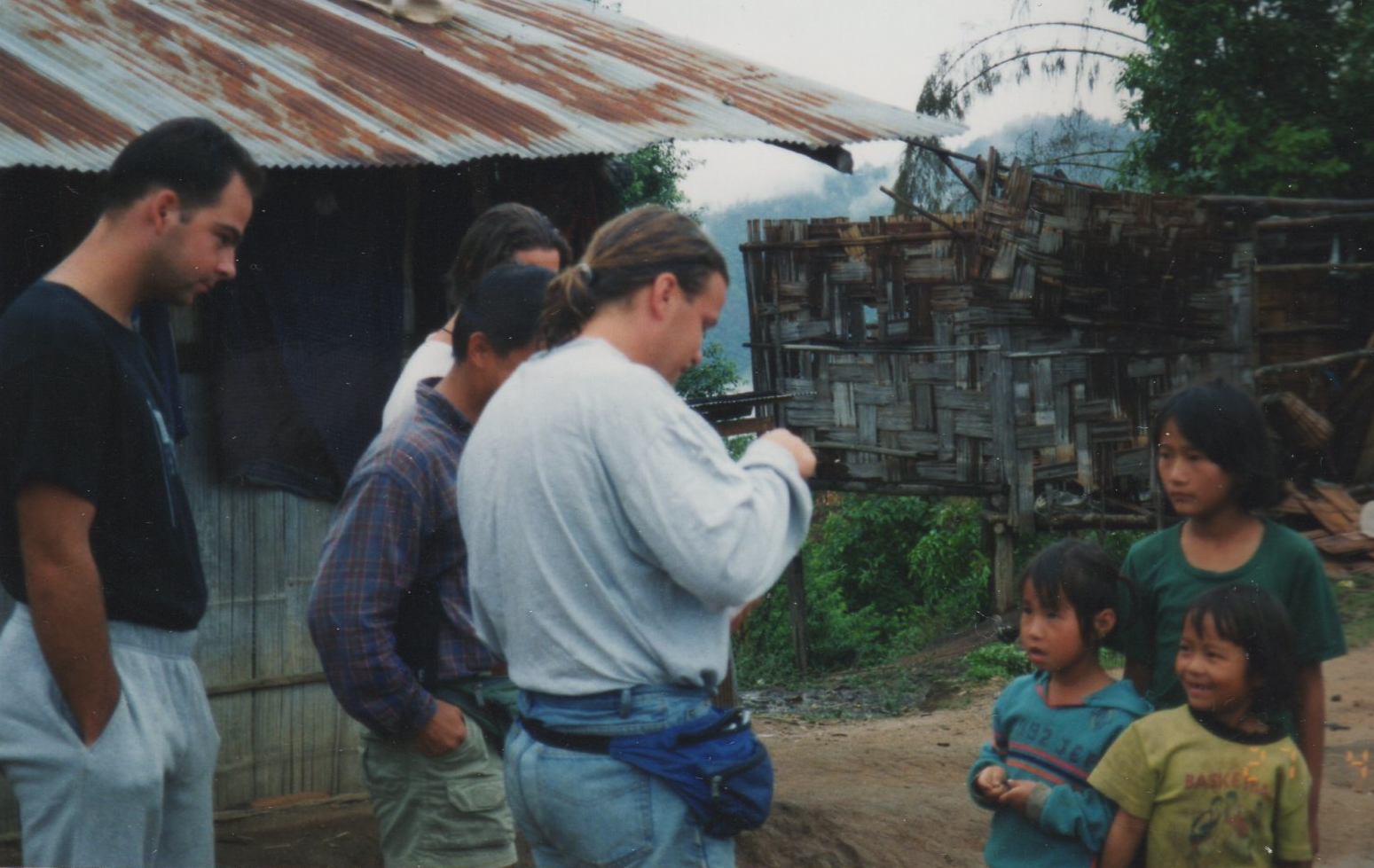

We arrived at the tribal village, our stopping point, a few hours before we were to eat dinner: pork fried rice. Most of us used our free time to explore the village and taking pictures.

The hill tribe village turned out to look the way you would expect: a small settlement filled with basic, hand-made wooden shacks where the area’s families lived. As members of the group walked about; we were surrounded by small children following us around asking questions and begging for money they could spend in a small village store. We also saw members of some families working, a few others hanging out in front of houses.

As I walked by one house, a door opened and out stepped…a Caucasian guy with a beard. It wasn’t the beard that shocked me; it was the fact that there was a white man living in the midst of an all-Asian tribe. It wouldn’t have been surprising if he had been just a visitor, but he wasn’t staying in one of the shacks reserved for visitors. Still, it didn’t seem politic for me to say “Hey, white boy, what are you doing here?” especially when I’m white myself. Instead, I hung out and talked with him in hopes that some explanation would be forthcoming. Then, two more white guys appeared and I couldn’t resist. I had to ask.

All three were scientists collecting insects for the Czech Republic’s National Museum in Prague. They eventually invited several other backpackers and me into their quarters to show us their specimens, which included all varieties of creepy crawlies including spiders, rodents and a few of the beetles that seem to be so popular in this part of the world. They had come to Thailand to collect a specific specimen but couldn’t because the weather wasn’t right, so they were making the best of a bad situation by gathering whatever they could while they waited. They didn’t have much choice given that they were freelancing for a museum that didn’t have enough money to pay them, but would pay for what they brought back. If they went back empty-handed, they wouldn’t make any money. They never really explained why the national museum of an Eastern European country would be interested in bugs from Southeast Asia, however.

We probably would have gone on chatting for quite some time if one of the neighbors hadn’t interrupted to invite the Czechs to dinner. Although it was an invitation I would have jumped at, they politely refused.

“We said no because we know they’re serving pork and the pigs here are infected with trichinosis,” he said.

There was a moment of silence in the room as the import of what he had said sunk in. You could see the realization in the face of each of the hikers. Our dinners were being prepared in the village, the dish contains pork, and THIS IS NOT GOOD. We all breathed a collective sigh of relief when the scientist assured us we wouldn’t get sick if we ate around the meat. All we had to do was find a way to warn the others and figure out how to eat around the pork without appearing rude or ungrateful. Some scattered the chunks of meat around the plate to make it look like they just missed them, a few said they were vegetarians. I hid the chunks behind clumps of rice.

Then, we spent the rest of the evening talking, playing charades, smoking opium (which the government allows villagers to do), and sleeping on the floor.

It wasn’t until the next day that our guide told us he had purchased the pork at a market when we stopped for lunch.

The second day of the hike taught me why cars replaced elephants as the most popular form of transport in much of the world. It’s difficult to find a saddle (or even bucket seats) big enough to fit (let alone be comfortable), the pick-up is terrible, the handling is mushy and the gas mileage is so bad it’s not even worth mentioning. And then there’s the whole water-spitting thing.

Since it was hot, I wasn’t surprised when the elephants stopped to refresh themselves by blowing water through their trunks. I didn’t mind the lack of a windshield because the water was refreshing. Being that the elephant we were riding on was the youngest of the bunch, I found it cute. It was like seeing a kid who had been born with a hose attached to his body playing with it to see how high the water would shoot and how far back it would go. I was less amused when my seatmate reminded me we were on dry land and the only place the water could be coming from was inside the elephant itself.

Riding the youngest elephant has advantages and disadvantages. On the positive side, it was faster than its companions and we spent much of the ride at the front of the pack. The negative side is that the animal was more rambunctious than the others and would gallop away from the group at fairly high rates of speed for a tame elephant, taking us along for the ride. I wouldn’t have minded if he hadn’t shown such a penchant for charging tall trees with low-hanging branches. It may be hard to imagine being frightened and amused at the same time until you have sat on an uncomfortable wooden bench on the back of a large animal lumbering along at 15 or 20 miles per hour– headed directly at something you know is going to knock you off. It’s like being tied to a chair on the top of a semi heading for an overpass with just enough clearance for the truck to pass under: there’s nowhere to go. I don’t mind playing chicken, it’s just that I want my opponent to face some consequences if he doesn’t swerve at the last minute, even it’s just smashing into me. Maybe it’s silly, but I’d prefer to have some say in my own demise.

We ended our elephant amble in a tribal village where we were to board homemade bamboo rafts and float down the river to our destination the next morning. While we waited for dinner, we began debating decriminalizing drug use. Although I was one of two people who had not smoked opium the night before, I defended legalization while Dick, who had never tried drugs until the night before, opposed legalization. The debate raged on until we called it a night. Because I was sleeping on a hard wood floor with a group including two snorers, I didn’t get much sleep. The only one who slept well was Dick who crashed shortly after he took the first few hits of marijuana he’d ever had then stoutly insisted that it wasn’t effecting him at all. It had so little impact on him we had trouble waking him.

Whenever I think about the final half day of the trek, I think about Deliverance. There weren’t any gun-toting Appalachian-style Asians telling us how pretty our mouths were, ordering us to squeal like a pig or any freakish-looking children playing dueling sitars, but there were distinct similarities. As in the movie, the day started out with joy and silliness, but took an ugly turn. The best that can possibly be said about this segment of the trip is that “a good time was had….by some” and, more importantly, “no one was killed,” a yardstick against which I now measure all leisure activities.

Since there were too many of us for one raft, we used two. As we floated downriver a friendly rivalry developed. Passengers splashed the enemy raft, used oars to push the rafts off course and tried to pull people into the water. I even stole an oar from the enemy. As the light-hearted war raged on, we entered a series of rapids that didn’t seem all that threatening.

Until we got stuck.

We were so busy screwing around we didn’t notice the rock rising out of the water’s surface until it was too late. We hit it broadside and the raft became lodged underneath. The impact sent one of the passengers flying into what had once seemed like fast moving water but now seemed increasingly treacherous. The harder we tried to pull the raft up and away from the rock while we stood in chest-high water, the harder the rapids pushed the raft into the rock. After spending several days pulling, we were finally able to free the raft, but the effort cost us a pontoon.

Then we lost a passenger.

The Wisconsonian went flying when his oar lodged in a rock on the riverbed and took him with it. He wasn’t injured, but he had jammed his fingers and couldn’t row, leaving us with one less person to man the battle stations the next time we passed the enemy craft.

We got the last laugh, however, when the other group’s raft ended up sideways in front of us after it cleared the next set of rapids. Since the craft suddenly floated into our path, we couldn’t make any evasive maneuvers and rolled right over them. Although both crafts remained seaworthy after the crash, the other group never bothered us after that.

Go figure.

The hike ended shortly after a lunch of sandwiches and soup before we headed back to Chiang Mai, forcing me to conclude again that all the effort seemed like a little much to expend just to have another bowl of soup. I also wondered what this region’s love affair with soup was all about. We got back to Chiang Mai just in time for the two Brits and me to catch a bus back to Bangkok, my final stop before flying into Vietnam.