Please Don’t Squeeze The Chairman: Dance Lessons, The Pork Dumpling Incident And Other Tales From the Dead Communist Leader Tour

If he knew,

What they’re doing to his wife today?

–From “Living in China” by Men Without Hats

Although the train was due to arrive in Beijing around 4:30 a.m., the conductors wanted to make sure all the passengers were up in plenty of time to leave. So they woke us up in 1959 when many of us weren’t even born yet.

No matter how light it is, it’s hard to get any sort of impression of a city at 5 a.m. In fact, the only impression I got was a funny one because the first thing I saw when I got out of the taxi at the hotel was what appeared to be a condom on the driveway of my hotel, causing me to laugh loudly as I walked in. After all, you’ve got to wonder how it got there, considering that most condoms are usually found close to the scene of the crime. I later found out that it was the wrapper for a Chinese version of a Popsicle without the stick.

By the time I got someone at the front desk to allow me to check in, however, I was too tired to ponder how an apparently used condom ended up on the driveway. I just wanted to sleep on a bed that wasn’t in a moving vehicle. Unfortunately, once I checked in and finally found the dorm I discovered that someone was already sleeping in the bed that I’d just rented. So I ended up sleeping fitfully for an hour until I finally gave up and went for a walk just after 6 a.m.

Having noticed a grocery store and McDonald’s across a small canal next to the hotel, I left to see if the supermarket was open. Although it was closed, the plaza in front was packed with people, some doing tai chi, a few sitting on benches with small children and a large group of men and women doing odd calisthenics to Chinese music. The exercises weren’t like any I’d ever seen, however, and the lines were much more segregated. After all, they weren’t exactly school kids or Orthodox Jews. In fact, most of the people who were responding to the commands the teacher was yelling through a bullhorn were in their 20’s.

After about five or 10 minutes of doing exercises with no real aerobic benefit — taking one step forward and backing up, pivoting, arm waving — the lines broke up and everyone paired off including the instructor, who grabbed a man who’d been standing on the sidelines minding his own business. And then she began yelling instructions through her bullhorn as she and her partner spun around. To Chinese music.

If I’d been back home I would have immediately realized that I was watching a ballroom dancing lesson, but it was so out of context it took me a half-hour to figure it out. Of course, the Chinese music didn’t help matters. If they’d played Glenn Miller or something more familiar I would have gotten it right away.

Seeing so many people up so early so tired me out that I needed to go back to the dorm and take a nice long nap.

I’m not sure why, but ever since the pro-democracy student uprisings in April 1989, I’d assumed that Tiananmen Square was a fully-enclosed fortress. I’d never seen any pictures that would indicate this was true, though. I just had this impression — perhaps because it was hard for me to imagine so many thousands of students sitting, standing and milling around in a square in the middle of a city without being a tremendous traffic hazard, which, of course, they were, but I had no idea how big a hazard.

The truth, of course, is Tiananmen is far larger than I could have imagined. At 123 acres, the whitish-yellowish brick area is the largest public square in the world, and it’s smack-dab in the middle of one of the world’s most populous cities. Because it sits between Mao Tse Tung’s Mausoleum to the south and the Forbidden City to the North (yes, it’s yet another Forbidden City now open to tourists. Asia seems to be so loaded with these places I’m beginning to wonder where people were allowed to go in the old days) and is bordered by large highly-trafficked boulevards on all sides, it’s easy to see that such a gathering represented a huge traffic hazard, even if the group didn’t spill out into the streets and block access to the Hall of the People to the west and the Museums of Chinese History and the Revolution. Although the plaza was at least five city blocks long, it was still difficult to imagine so many people gathered in one space for a week, even if China is one of the world’s most populous countries. The question of what so many people did for bathroom facilities boggles the mind. After all, considering how poorly much of the city was kept up and knowing that the protest was an anti-government uprising, it was hard for me to imagine Communist Party General Secretary Zhao Ziyang sending out for porta-potties. Seeing how wide the boulevards were, however, it was easy to imagine tanks rolling up. The streets surrounding the Square could easily accommodate eight lanes of traffic.

Seven years later, there were no signs of the struggle, no monuments, no plaques or even the slightest mention of the events that had riveted the world’s attention for weeks. There was, however, a nod to current events across the street at the Museums of Chinese History and the Revolution where there was a clock counting down the time to the return of Hong Kong. I’m not saying the country was eager to get its biggest cash cow colony back into the fold, but the clock wasn’t just counting down the days, weeks and months to go. It was also counting down minutes and seconds. I knew China’s government was looking forward to the change, but I had no idea how much.

The reason was obvious, of course, the group of islands referred to collectively as Hong Kong are cash cows. Because the city is unencumbered by the rules of Communism, it has become a gateway for commerce into and out of China. Like New York, London, Bonn and Tokyo, it’s a place where the world comes to do business.

Similarly, Tiananmen is where Beijing’s tourists come to do their business: gawking. And there’s plenty to see. In addition to Tiananmen Gate (which is actually across the street), the museums dedicated to the country’s history and its revolution and the Forbidden City, there’s also Mao’s Mausoleum and the Monument to the Heroes of the People. The statue is in a style that can only be described as early Communist people’s art and looks like something you might expect to see in Moscow’s Red Square complete with long lines of common people farming, teaching and taking up arms. In fact, the only real difference between this statue and its Russian counterparts is that the faces are Asian.

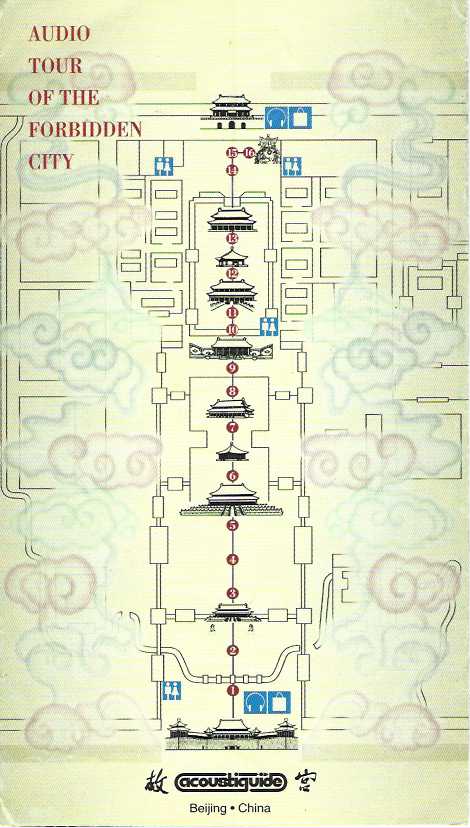

I could spend pages waxing poetic about the Forbidden City, but why? The former home of the country’s emperors covers so much territory it’s impossible to do it justice. Since I didn’t know much of the city’s history, or even what I was looking at as I walked through the palace, I rented a headset so I could listen to a tape tell me what I was looking at. Although I felt like a goofball from another planet because I was the only person using one, I got far more from the tour than I might have otherwise. To me, the best part was the narrator, who sounded like Roger Moore on sedatives.

Because I was on what I’d dubbed my “Dead Communist Leaders Tour,” I had to stop at Mao’s Mausoleum. Unfortunately, the whole short experience was rather sad. While waiting in line I learned that the Chinese don’t have the sense of humor about Mao that the Vietnamese do about Uncle Ho. Maybe it’s short man complex, but Mao’s final resting-place isn’t as much fun as Ho’s. It’s far more solemn and people are moved through much more quickly undoubtedly because the powers that be don’t want visitors to have enough time to trip across the dirty little secret I discovered while I was there: It isn’t really Mao at all. It’s Alfred Hitchcock with hair.

Like most big cities, Beijing is pretty dirty. The one thing this city has that most of the others don’t is a greater propensity towards spitting, hawking, hacking, coughing, sneezing, uncovered nose blowing and the spread of germs where ever possible. Everyone does it. I’ve seen students, businessmen and well-dressed, well-mannered women hawk up good ones whenever the need arises. It was so common I was shocked to see a woman spit into a tissue because most people just used the sidewalk, making Beijing a Singapore in reverse.

This doesn’t mean the Chinese weren’t trying to be more conscientious about the spread of germs. A man from Miami recalled a scene from the train he and his wife took to Beijing. When a passenger needed to spit he rolled down his window, leaned his head out the window, spit, closed the window…and then proceeded to put a finger over one nostril and blow his nose Arkansas hanky-style onto the floor.

What with all the spit, snot and overcrowding, I wasn’t surprised when a cold swept through the dorm where I was staying, going from person to person along the line of beds.

The dirt doesn’t mean the city isn’t orderly in its own way, however. Everywhere I turned I ran into a triplicate-fed, paper-powered bureaucracy the likes of which I hadn’t seen before or since. When I bought something in the Friendship Store (a store specializing in selling foreign goods to foreigners), for example, I couldn’t get the item right away. Instead, a receipt for the unpurchased item was written in triplicate. The counter clerk kept one copy and sent me to a register at the front of the store where I gave the cashier the second copy of the receipt, paid for the item and was given a receipt showing I’d paid for the item even though I already had a receipt. I then took the receipt back to another counter where I was given the item I had just bought. To me, this seemed like an awful lot of trouble to go to for a Snickers bar or a Roxy Music cassette.

The practice reached its most extreme at the Jing Hua Hotel where guests also get a receipt in triplicate when they pay for a night’s lodging. The front desk keeps the first copy, the second goes to the floor attendant to prove that the guest has indeed paid for the bed and the guest keeps the third part.

Heaven help the guest who misplaces that receipt and stays more than one night. I tried to pay for my second night’s stay right after I got up in the morning, but the front desk wouldn’t let me because I didn’t have my receipt from the day before. The hotel clerk wouldn’t take my money because she insisted I’d already paid. This concerned me because I knew the dorm was full and I worried I’d lose my bed. I even had visions of returning to the dorm only to find someone sleeping in my bed and my stuff nowhere to be found. When the staff refused to take my money, I said I wouldn’t leave until they promised not to sell my space.

They didn’t tell me about Helga the Enforcer.

Okay, so maybe her name wasn’t Helga, but that didn’t make her less intimidating. Then again, I tend to be intimidated by anyone standing over my bed in an imposing manner when I’m barely awake, no matter how big they are, especially when they are demanding that I hand over proof of payment. The 5’2″ woman seemed far less worrisome once I pulled my 5’11” frame out from under the bedsheets and off of my mattress, but her message was still disturbing because she wanted something I didn’t have. I told her the staff refused my payment the day before because they said I’d paid. I even told her I was planning to pay as soon as I got dressed, but she was having none of it and wouldn’t get out my way to let me pay because I didn’t have a receipt.

“So, where is your receipt?” she asked after I’d just spent two minutes explaining.

I shrugged my shoulders in what I thought was the international symbol for “I don’t know.” Apparently, it isn’t internationally understood because she asked again.

When I said, “No have” (which is international for “I don’t have it”), she said I would have to pay again if I couldn’t find it. This was fine by me because I would have been doing so at that moment if she hadn’t been busting my chops. I tried to explain this to her, but it confused her so much that we ended up spending five minutes arguing even though we were in complete agreement. Apparently, this confused her further. Frustrated and unable to overcome the language barrier, she finally took me to Room 218, the home of Su, an English-speaking travel agent who served as the arbiter of disputes involving foreigners. Once I explained the situation to Su, he called the desk, yelled into the phone, slammed the receiver, said the problem was fixed . . .. and asked me to fill out more paperwork.

Su also apologized and offered to buy me a beer. He didn’t offer to give me a discount for my troubles, but I didn’t mind. I was just happy he was willing to apologize for a problem that wasn’t his fault. It was a surprising contrast to New Zealand where Magic Bus management had refused to apologize for its mistakes. Su also told me that I was partly at fault because I hadn’t read a bulletin board near the front desk explaining how the system worked. He was so polite about it that I didn’t have the heart to tell him that it took two days to find the board.

This should have been the end of the story, but it wasn’t. The front desk still insisted I had paid for Tuesday but, rather than running the risk of inflicting the wrath of Su, they agreed to let me pay $7 for a bed for two nights and then wrote a receipt covering payments from June 12th through 14th. Initially, Su didn’t see a problem with the receipt until I explained that it covered Wednesday and Thursday, but didn’t mention Tuesday, at all, putting me back in the same situation. He took my receipt, told me he would take care of the problem and thanked me for my honesty. Although I’m basically an honest guy, the truth wasn’t the only thing that drove me to do what I did in this case. “I just don’t want to have somebody standing next to my bed tomorrow morning asking me why I haven’t paid.”

Another strange custom I noticed during my visit was the way most Chinese enter buses and subway cars. The phrase “piling on” comes to my mind. I had heard that Chinese mass transit riders don’t like to wait for vehicle doors to open. Instead, they push into a doorway at the same time in an effort to find scarce space before anyone else, but I didn’t believe it. The rumor seemed to go against the rules of civility necessary to live in a big city. After all, New Yorkers push and jostle to get into subway cars, but they don’t take running starts the way I had heard the Chinese do. Being a person who doesn’t like to generalize, I was still stunned when I saw it for myself.

It was not a pretty sight.

The rush to board buses, trains and subway cars doesn’t resemble a stampede so much as a scrum during a rugby match. In the split seconds before doors opened, I saw commuters backing up slightly and taking running starts as they pushed into the crowd. Others just smiled, demonically, as they rammed the crowd with their bodies. Most seemed to enjoy the competition of the thing, as if it were a sporting event in which the spectators got to play for valuable cash prizes.

Or seats.

The experience taught me that, in China, the front of the line is no place for a timid person, even if the person is taller than the rest of the crowd.

The problem with writing about the Great Wall of China is that anyone who has ever visited China has already seen it, knows more about it than I do and will be able to tell if I’ve gotten it wrong, so I’ll have to make shit up. At the same time it’s impossible to explain the scale of something that runs across 4,000 miles of countryside, was built by 300,000 forced laborers, is more than a thousand years old and was obviously built by aliens from far off planets like Mars and Indonesia.

As I quickly learned, it’s not enough to say you want to go to the Wall because it’s so big you have to decide where you want to visit, especially if you want to avoid over-touristed areas. As a result, people in the know told me, I might not get as uncrowded or unspoiled a view of the wall as I would want. Imagine that. A country of 70 jillion people and I might not escape the crowds. Now, there’s a puzzler. Fortunately, I am not one of those picky people when it comes to wall watching. Although my travel agency’s brochure says Mutianyu is one of the best locations to get away from the tourist scene, I went to Scimitai because the Jing Hua offered a bus there, and because Su said it was an unspoiled section of the wall, making it sound like I could go to my grocer’s freezer and determine which part of the wall was fresh and which wasn’t.

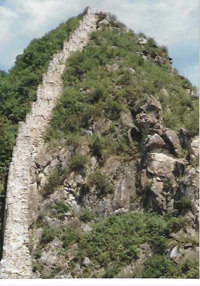

I can’t say much about freshness, but I can say that most of walkway on the top of the wall of this section is in extremely bad repair (LP calls it the worst, most dangerous stretch). The route is quite treacherous because there are many steep grades where the bricks have worn away, and there are few toeholds. The walkway’s grade on one worn down area was so steep that walking was closer to mountain climbing than hiking because it went straight up. The return trip is worse because the grades are so steep I ended up sliding on my butt most of the way.

Part of the cause of the wall’s decay is age. If you build anything then leave it sit out for a thousand years without maintenance, it’s bound to crumble. Peasants in towns and villages haven’t helped manners much because they have seen the wall as a free building supply store where they could pick up bricks for their houses and barns. One guidebook I read even claimed the army built barracks out of stones from the wall during the Cultural Revolution of the 1970s.

Even without all its original equipment, the wall and its views are quite spectacular. The architectural marvel winds like a serpent over the country’s hills beyond the line of vision in both directions, making it appear like it goes on forever.

I walked farther than visitors are supposed to, but I didn’t realize I’d done so until I was heading back to the entry point and saw the “Danger, Do not Enter” signs. But, then again, visitors to this section of the wall aren’t really supposed to walk all the way back to where they started. Instead, they are supposed to get on an expensive tramway and ride it to the ground. It’s so nice this section of the wall isn’t touristy.

To celebrate our visit to the Wall, a woman from Colorado, another guy from the States and I went to a restaurant that he said had great, cheap noodle dishes. It took us 20 minutes to order because we tried to do it using the Coloradan’s Mandarin phrasebook. Apparently, the waitress knew we were American because she didn’t bother to ask what beer we wanted, she just brought us a big bottle of Pabst Blue Ribbon. Although I don’t really like beer much, I was so thirsty I found it to be tasty indeed. I think all three of us enjoyed it immensely until we poured a second round and saw something floating in the bottle.

The best part of the meal came when three Chinese children at the next table came over to play. Whenever one of us made a face at them, they would imitate us. They also made the same sounds we did. I took full advantage of the situation when I quoted Groucho Marx from “A Night at the Opera,” saying, “Boogie, boogie, boogie.” They said it right back. Then I did an imitation of a Model T horn (“Ah-ooo-gah”). Since they didn’t know I made the sound by breathing in rather than out their version sounded odd, but was still quite funny. I’m sure their parents loved me when they got home and their kids said “Ah-oo-gah” all night.

There was a scary moment when we noticed that the meat in the beef stir-fry was pinker than we liked, but we ate it and lived. The experience was far less frightening than the one I had at dinner the previous night, however.

It all started when I stopped at the restaurant next door to this one. I went to the other because I thought it was the one the American man mentioned when he recommended a good, cheap place to eat. I suppose the lack of customers should have been a hint, but I just figured I was following in my grandparent’s footsteps and eating supper several hours early to avoid crowds and get the cheap seniors meal.

The owners invited me to sit at a table out front and watched me eagerly, waiting for my order. Since I didn’t know what they had, I asked for a menu, then realized the request was pointless because the it was all in Chinese. (It may have been a strange time for this realization to occur to me after almost a week in Beijing, but it was then that I realized that every eatery there is a Chinese restaurant and everyone serves Chinese food, even if it doesn’t. For example, McDonald’s is a Chinese restaurant that serves food to the Chinese, or Chinese food).

Recalling that he had told me about the restaurant’s specialty, I requested it and hoped they would understand.

”Noodles?” I asked.

First the waitress and her brothers stared blankly then all began speaking to each other rapidly in Chinese.

“I don’t understand. I don’t speak Chinese,” I said.

Then the waitress pointed to the menu and said something that I didn’t understand.

“Bee bo bab o beeble bop?” she asked.

“Noodles?” I asked again.

So the waitress picked up a piece of paper and wrote in Chinese. This was a new take on cross-cultural coping. When Americans are confronted with blank-faced incomprehension they believe it will make sense if they just speak slower and louder. If the restaurant is any indication, the Chinese believe that if a person doesn’t understand what is being said he will understand it when it is written down even if the person doesn’t speak the language. So the waitress wrote it down and showed it to me.

“Bee bo bob bo beeble bop?” she asked, as she lifted the piece of paper containing chicken scratch and pointed to it.

Ever accommodating, I took the paper and pen, stared at the page for a minute, then followed her example.

“Noodles?” I wrote in English.

The waitress pointed to a dish on the menu. I asked how much it was. She said 16. I thought about it for a moment, asked what it was, got an answer I didn’t understand, ordered it and prayed it was edible and that I wouldn’t die.

Right at that moment I looked around and realized that I was the only diner in the restaurant even though the one next door was packed. And then I knew I was going to die because even the locals knew something I didn’t.

While I waited for my order, the waitress’s family and friends gathered around, tried to talk to me and then wanted to look at my journal, which they flipped through reverently even though they couldn’t understand a word I’d written. When one came across what was obviously an address, he pointed to it, said “Girlfriend” to all his buddies and they all laughed and nodded knowingly until I pointed out that Martin was a strange name for a woman.

Then one of them asked what I ordered. I’m not sure why, but the waitress decided to spell it in English.

“P-O-O-K,” she said.

“You mean pork?” I asked.

“Yes,” she said.

Moments later another woman carried out a plate of pork dumplings. At this point it was too late to do anything else, so I ate them.

They were delicious. And I didn’t die.

As I was leaving after paying the bill, another waitress in the restaurant said, “Sank you very much.”

And we all laughed.