An Irrational Security Risk

Who got arrested down in old Hong Kong,

He got 20 year’s privilege taken away from him,

When he kicked old Buddha’s gong….”

—From Hong Kong Blues by Hoagie Carmichael

The look of panic on the face of the clerk at the Chinese Consulate in Hong Kong said it all.

I like to call the expression she gave me “The McDonald’s Stare” because it’s the same look you get when you have a special order at Ray Kroc’s place. Whether the request is a fish sandwich without cheese or “two all beef patties special sauce, lettuce, cheese, pickles, onions on a sesame seed bun, hold the sesame seeds,” the response is the same. The smile drops off the cashier’s face so fast you can hear it hit the floor, the eyes go blank and sweat beads on the forehead until the worker realizes she can call in a manager. In the seconds before the problem is passed on it appears that the worker’s brain will short circuit a la “The Stepford Wives” and she’ll say “I thought you were my friend. I thought you were my friend….”

As the endless, sweaty seconds passed, I quickly realized that China’s Communist government was like McDonald’s. After all, McDonald’s slogan isn’t the democratic “Have it your way.” It’s the more autocratic “McDonalds is my kind of place” (not “Your kind of place”). Similarly, I’m pretty sure China’s government’s slogan would be “Have it our way.”

As I stood at the consulate counter, I was puzzled because I couldn’t recall placing a special order. I’d just completed my request for a visa the same way I had in other countries, filling out name, address, telephone number, passport number, profession. . . . . oops. I’d foolishly written “freelance writer,” which set off a series of alarms that I’m sure a person from a country with a free press couldn’t even begin to understand. Although I had decided not to write “journalist” on application forms even before I left the U.S. I had forgotten when I applied for a Vietnamese visa. Even though Vietnam is the region’s only other Communist country, government functionaries let me in without blinking. It was my Frank Zappa tape that frightened them.

If I had expected problems anywhere it would have been Vietnam. The country was still so Communist it stopped approving visas and wouldn’t allow in foreign visitors when the party faithful held their annual convention (which began shortly after I left. I’m pretty sure my departure and the closure were unrelated, unless the officials sent the country in for its annual pressing and cleaning).

After asking what I wrote about and requesting a few writing samples (which I didn’t have), she took my passport and conferred with her superiors in a backroom. Yet another similarity to McDonalds. Then she told me she couldn’t give me a visa and the only way I could get one was through a travel agency. I told her I only wrote about oil and hardware stores, but she wouldn’t budge.

This was not good news because China’s capitol city was the most convenient terminus of the Trans-Siberian. Without the visa my dreams of riding the world’s most famous train would collapse, ruining part of the trip.

I called the travel agency I was booking my trip through to see if a representative would write a note on its stationery saying I was in a group tour. Unfortunately, it was noon and the only person in the office had just started work that week and didn’t know. I was caught in a catch-22: I knew I might not be able to get the letter unless I bought a ticket; on the other hand, if the agency wouldn’t write the letter, or the Chinese Consulate rejected my application anyway, I would end up spending a lot of money on cancellation fees.

When I called the travel agency, Moonsky Star, an hour later, a veteran agent said the firm couldn’t write the letter even if I had a ticket. Instead, he suggested having an expediter get it for me or filling out the application again listing a different occupation.

“We could make you a tea boy,” he said.

This was typical of my experience in Hong Kong less than a year before the British returned control to the Chinese. Although Hong Kong was a “can-do” kind of place where business was a religion and getting things done expediently wasn’t just a good idea, it was the law, it always seemed like I spent most of my time dealing with unexpected complications in simple plans. When I went to Moonsky Star, the agency that specializes in booking passage for backpackers on the Trans Siberian I learned I had to catch the train in Beijing. This came as a complete surprise to me. After all, why is an agency known for booking passage on the train hundreds of miles away from where the train stops. Yes, I should have known better, but I never claimed to be the smartest backpacker on the block.

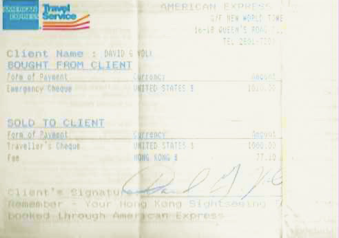

Then there was the matter of paying for the tickets. The six-day train trip itself was a steal at $349, but didn’t include the cost of the Russian visa application, passport photos, the train to St. Petersburg, a one night stay at a two star hotel in Moscow or two nights’ stay in St. Petersburg (all required). The agency also offered to book a train to each passenger’s next destination after St. Petersburg. The service was a courtesy that allowed customers to avoid the Byzantine world of ticket purchasing in Russian train stations. It was still a bargain at $550, but paying for it wasn’t; the agency didn’t take traveler’s cheques or credit cards.

Thank God for banks with good exchange rates, ATMs, American Express Travel Service offices, and a country where banks give cash advances on AmEx Cards.

Then there was the difficulty of finding an affordable room. Kowloon’s Chung King Mansion may be a well known backpacker hangout filled with hostels in many price ranges, but none were cheap–even dorm beds were expensive, and many of them were pretty dodgy. Still, my guidebook insisted it would be possible to get a single room with a phone for around $28. When I informed managers of this fact, they laughed and wished me luck. The only reason I wanted the phone was so I could check my e-mail. I later found another backpacker who asked to use a phone for just such a purpose at an international hotel, and had offered to pay for it. A desk attendant told him he would have pay $200 for a room, proving once again that it may be great to be in a global village with an information highway, but only if you can find an on-ramp.

I ran into an even stranger complication in the Jewish community. Figuring a country’s Jewish population always gets the brunt of it during a transitional period, I wanted to see how fellow Jews were faring facing the impending uncertainty. I thought the best way to find out was to attend Saturday morning services then and talk to people during the post-service reception.

That was the plan. Security had other ideas.

Although the mostly Asian security force acknowledged I did indeed look Jewish and was not packing any weapons, members of the elite force wouldn’t let me meet the community because I wasn’t a member of the Jewish Community Center and because I was so late that services were already over, never mind that the congregation was eating lunch one floor below where I was standing. I’d heard of congregants giving latecomers grief, but this took scolding to a whole new level. No matter what I said, they weren’t going to let me go downstairs. I was just as persistent as they were, however, and they finally asked the facility manager to come talk to me. I’m still puzzled why they didn’t call the police on me. Maybe they thought it would be bad publicity for a JCC to arrest a Jew. Then again, maybe not.

Ironically, I had easily gotten into the Center the night before and set up an appointment to interview the wife of the Reform congregation’s rabbi. Not only was she not in evidence, but the Reform Jews hadn’t bothered to tell the Orthodox Jews who used the facility I wanted to attend morning services. I later realized the oversight wasn’t the result of a communication breakdown. Instead, it was more than likely due to the fact that the Orthodox Jews didn’t like sharing the center with Reform Jews because they weren’t Jewish enough. Which proves the old joke is true: Two Jews, three synagogues.

Clearly, this isn’t the most welcoming way to run a JCC. After all, security is supposed to protect you and keep bad guys out while letting your own people in. That wasn’t what was happening in Hong Kong, though. Instead, security was keeping visiting Jews from actually visiting the Jewish Community Center. Or maybe just this Jew.

There were some in the community who might say such stringent security is a good thing: I wouldn’t. If they were keeping me out they were also keeping out other Jews who might be in need of spiritual guidance, regardless of social status. They were also keeping out potential future members and big donors, as well, but I’ve always been surprised at how resourceful the rich really are.

Even from a historical perspective, the security was excessive. Except for that period of unpleasantness involving the Japanese in the 1940’s the community has never been under threat, but you kind of expect that from conquering enemy forces. It was nothing personal, mind you, it was just that most of the Jews had sympathized with the British and you couldn’t have really expected the Japanese to be good sports about it, now could you?

I think the Community Centre’s biggest mistake was hiring an Israeli consultant to set up security. Israelis are experts because they have to be. They live in a dangerous neighborhood. The neighborhood surrounding the Centre in Hong Kong is nowhere near as threatening. Despite the three security guards working the front desk at 24/7, an abundance of surveillance cameras and a small cache of weaponry on hand, I was told Israeli consular officials still thought the security system was far too lax.

I think the security was a bit too tight, especially when you consider a message on the home page of the Centre’s web site: “Our Centre welcomes Jews from all over the world. So whether you’re living in Hong Kong, planning to live here or just coming for a holiday, pay us a visit.

“You’ll always be welcome!”

I’m not saying some paranoia wasn’t understandable. The island was due to return to control of the People’s Republic of China on July 1, 1997 and no one really knew if or how the Chinese would change things. The only thing members of the Jewish community knew for sure from history was that the Jews always got the worst of political upheaval. People always need someone to blame when things go bad and the Jews have always been a convenient target ever since they killed Christ, began engaging in ritual sacrifice of small children, launched the tri-lateral commission, wrote the “Protocols of the Elders of Zion,” formed the Zionist Occupation Government in the U.S. and then bought up all the media.

I’m kidding of course and I can prove that at least two of those old wives’ tales are wrong, wrong, wrong. For starters, I know the ritual sacrificing is just a slur because none of the people I know have ever been able to develop a taste for small children. Additionally, if the Jews own all the media, how come I haven’t been able to get a job at a newspaper or magazine.

The city’s Jews were split on whether the takeover would be good or bad. When I finally got into the JCC, the head of the Orthodox Jewish community, Rabbi Samuel Lopin, told me one of the biggest concerns was the government’s view of religion. Many believed government wanted complete loyalty from its subjects, and saw religion’s emphasis on a higher power as a threat. At the same time, many in the community were optimistic because the Chinese respected what they saw as the Jews’ business acumen (one of the few times a stereotype worked in anyone’s favor) even though the Communists didn’t really understand the religion.

After having told me about community’s concerns, he also told me that most people weren’t even talking about the turnover or how they felt about it. He did say that many people had just up and left without telling anyone. In the few instances when he ran into people who were beating a hasty retreat and asked why they were leaving, they all mentioned logical reasons and denied their decision had anything to do with the coming change.

Lopin’s contract was conveniently scheduled to end just before the handover and he opted not to renew.

It was a measure of this community’s faith in the future that they had already begun auditioning a new rabbi and hoped to have a new one before Lopin left.

About the only sign of the impending change that I noticed in June 1996 were souvenir t-shirts that not only mentioned the date 1 July 1997, they also mentioned the day. Otherwise it seemed like any other capitalistic Western city where business is a religion and commerce is king. I don’t know what the queen is, however. Maybe commerce never got married.

Hong Kong didn’t look like a city in crisis. Building was proceeding so frenetically that most of the buildings on the hill overlooking the Harbor from Hong Kong island were multi-story skyscrapers, and more were going in where ever there was a spare space. It looked like there was so little room to expand horizontally that they were expanding vertically. The impending deadline seemed to be driving the frenzy. It was almost as though everyone so feared the takeover that they wanted to get their work done so they could take the money and run. Or maybe they just thought the change would result in such negative business conditions that building wouldn’t be possible later on.

Regardless, the orgy of building had turned Hong Kong and Kowloon from places where it was once possible to get harbor views from an apartment balcony to areas where the only way to expand was up, creating a shiny forest of glass and steel where the skyscrapers were the trees. While the beauty of the harbor kept it all from looking repulsive, Hong Kong residents told me that the city of fictional character, Suzie Wong, is long gone and what remains is far too expensive for most average people to rent.

One of the ways people were hedging against the crisis was to take out huge bank loans, so that if China confiscated private property, it would have been the bank’s problem, not the borrowers’. The banks knew this, of course, and were making buttloads of money.

In true trickle-down fashion, rent prices forced everything else up. Lodging, entertainment, food. Ironically, it was cheaper to eat at a fast food chain like Wendy’s, Burger King or McDonalds than it was to go to a locally-owned restaurant. This was strange to me, given that in all the Southeast Asian countries I’d visited before Hong Kong, local food had been cheaper than Western fast food. I’d assumed this was true because of the cost of bringing it in from corporate headquarters. The opposite was true in Hong Kong, however, perhaps due to its status as a transportation hub and business center.

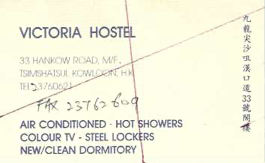

Lodging also left much to be desired. Granted, you can’t expect a lot of extras at the low end, but there’s no need to be rude. The first place I stayed in the combination dumpy-shopping-center/backpacker repository on Kowloon called Chungking Mansions wasn’t bad, but it was too expensive. Again, $30 may not sound like much in a crowded, popular city, but it is if you’re traveling on a limited budget. To save a few bucks I moved to a dorm room on the first floor of Victoria Hostel, just two blocks off Nathan Road, the main drag running through Tsimshatsui, the tourist area of Kowloon.

LP called it “one of the nicest hostels in Hong Kong.” It said nothing about the owners, however, and that was too bad. The owner slept until noon, listened to loud videos late at night, even though his television set was on a wall next to one of the dorm rooms and his assistant would come into the dorm after midnight every night and turn out the light without warning–even if everyone in the room was awake. In fact, there was one night when I was up until 2 a.m. talking to my dorm room mates, five Canadians on leave from teaching English in Korea, when the assistant walked in at 1:30 and shut off the light. When I complained he said there were people in the room who wanted to sleep. He had the wind taken out of his sails when everyone in the room disagreed with him, saying, “No we don’t” in unison. He then explained it was one of the hostel’s policies but couldn’t show us where the rule was written, even though all of the rules were posted over the registration desk.

After a day’s delay, I tried trickery to resolve my visa problem. After years of hearing comedians joke about how Chinese waiters all look alike, I thought the reverse might be true, too, especially among consular bureaucrats who see thousands of big, dumb Western faces every day. To help the process along, I did more than just change my profession to office worker, I also changed shirts, messed up my hair, removed my glasses, left my daypack at the hostel and I waited until after lunch to return. Although I chose a different bureaucrat’s line this time, his window was right next to that of the woman who had rejected my first application. By now the butterflies in my stomach were playing Ping-Pong with the aspirin I had taken before lunch, but I was as calm as possible when I handed over the form and a passport-sized photo. The functionary briefly looked over the form, looked at me, looked back at the form again, then stamped it without comment.

I was free to go.

And I was free to enter China.

Now, all I had to do was buy provisions for the six-day trip.