Danger, There’s a Shakedown Dead Ahead

Her:”How is your day going?”

Me: “Pretty good.”

Her: “No, it’s not.”

–From an exchange with an attractive accomplice.

I should have known there was going to be trouble in Bulgaria when border officials pulled my two compartment mates off the train and only returned one.

It was their own fault. The college-aged American and Brit of indeterminate age thought they would be able to cruise through Yugoslavia without transit visas. Border officials pulled them from the car and told them to take their worldly possessions. After 20 minutes, the Yank returned, the Brit did not. He was undoubtedly sent back to Budapest where he would have to wait to get a visa.

Suckage.

Both of us were awake by the time we crossed into Bulgaria and passport officials asked us if we were passing through or staying in Bulgaria.

“Transit?” one of the men asked me.

“No, I stay,” I said.

It’s amazing how incredibly stupid you sound sometimes when you write your conversations down on paper.

The border guard stamped my passport and signed it but did not give me a statistical card, which my guidebook said tourists need. The government required hotels to stamp the card each day a person is in country so they can track his movements. The policy was a remnant of Communism in a city that hadn’t completely thrown off the shackles of the old system. On one hand, the government still appeared eager to to track the movements of foreigners. At the same time, the border guards I dealt with seemed reluctant to use them.

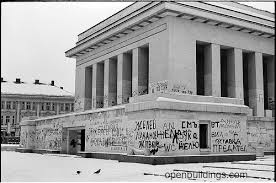

Like most major Communist capitals, the city had a prominently located mausoleum for one of Communism’s All Stars, Georgi Dmitrov. Unlike most similar cities in the former Soviet Bloc, this mausoleum wasn’t guarded because there’s no one to see. Government officials removed the body and cremated it in 1990 after anticommunist protests mounted following the fall of the Soviet system. The move left the white stone building with nothing and no one to protect it from the elements, bums and graffiti artists.

At least, I didn’t think anyone was guarding it.

That was before the man in the uniform caught me climbing around on the once and former sacred landmark.

Call it morbid curiosity, but I had to see what the building looked like close up.

Regardless of whether it was Uncle Ho in Vietnam, Mao in China or Lenin in Russia, all of the Communist countries I’d been in had mausoleums containing their taxidermied leaders and all were guarded by tight-assed, goose-stepping military body guards who apparently hadn’t been informed that their boss had died. I don’t know if it was because they were pissed they hadn’t seen the big man in years, they were upset that he never took them to dinner, or they were irritated at having to wear their dress uniforms in mind-numbing heat, but they wouldn’t allow tourists to touch the buildings or come close to the individual landmarks if they weren’t doing so reverentially. So, when I saw this unprotected building, I had to snoop around.

It wasn’t pretty. Although I couldn’t get inside the mausoleum, I could tell the building had gone to seed. The outside walls were filled with graffiti, there were liquor bottles scattered among the building’s columns and the smell of urine made it apparent that bums had turned it into a public bathroom. I may not have been impressed, but at least my curiosity was satisfied as I descended the stairs leading back into Sofia’s City Gardens.

That was when I ran into the uniformed man on the stairs. He was yelling in Bulgarian and didn’t look happy.

Assuming he was upset over my trespassing, I apologized profusely, said I didn’t see any “no trespass signs” — of course I hadn’t because if I’d had seen it, the sign would have been in Bulgarian and I wouldn’t have understood it — then continued walking down the stairs.

Although I don’t speak Bulgarian, somehow I could tell he was saying the local equivalent of “You’re not sorry, you’re coming with me,” stopping me dead in my tracks. If I’d been smart, I would have run. He was young and I was carrying a backpack, but I don’t recall his having a gun, so my five-stair head start should have been enough to outrun him. Instead, I was so shocked by the threat in his voice that I just waited.

And so the scam began.

The policeman took me to a parked yellow car where another man in uniform was giving three Japanese women their passports. When they asked me why they’d been taken to the car, I shrugged and said, “The best I can figure is that we’re in trouble for walking around on the mausoleum.” They appeared satisfied, gathered their passports and left.

Their ordeal may have ended, but mine was just beginning.

Once we arrived at the car the men demanded my passport. Foolishly, I complied without asking for identification because they seemed authoritative. Of course, even if I had requested their id’s, I don’t know what good it would have done. They could have produced id’s from a box of Bulgarian Cracker Jack and I never would have known the difference because it would have been written in Bulgarian and could have said “this card entitles the bearer to one free can of whoop-ass” and I would have been none the wiser. They spoke to me briefly in English without telling me why I’d been detained or reading my rights (apparently, in Bulgaria, tourists have no rights), then the first man passed my passport to his accomplice and wandered off, leaving me cooling my heels.

After a few minutes the accomplice looked at me and said, “Wait one moment.” Yeah, right. Like I’m going to leave while you’re holding my passport? I don’t think so.

If they were trying to intimidate me, they weren’t succeeding. I was concerned, but I’d been traveling so long that I’d lost a neophyte traveler’s fear and was too tired to care. Besides, if I could survive the paralyzing fear of death by chicken chunk, I could survive anything.

When the first man returned five minutes later he had an attractive woman with long red hair by his side. She approached me and spoke in heavily accented English.

“How is your day going?” she asked.

“Pretty good,” I replied, nonchalantly.

“No, it’s not,” she responded.

This was news to me. Granted, I had spent most of my first day-and-a-half in Sofia getting lost. The street names, which were all written in Cyrillic, had changed so much since my guidebook’s map had been published that I spent most of my time looking for streets that no longer existed. I may have been agitated and ready to move on to another city, but I didn’t consider it a particularly bad day. And I figured I would have been the first to know.

The woman then informed me she just happened to be in town from Plovdiv for a beauty seminar sponsored by a cosmetics company. She also said she was a friend of the men who hadd detained me and that she would translate because she spoke better English. Then, the real fun began.

The first man looked at me, held up my passport and said in English, “You can’t stay.”

The woman then translated for him, saying, “You can’t stay.”

“Why not?” I asked, looking at the first man.

“He asked ‘why not?'” she said, in English, to the first man.

At this point I realized I was locked in a four-man Abbott and Costello routine and just strapped myself in for the ride. The gist of their argument was that I couldn’t stay in Bulgaria because I didn’t have a statistical card. I told them I didn’t have it because the border agents wouldn’t give me one even though I requested it. Looking back on it, the argument was pretty stupid because, if I understand the policy, if I had been given a card I wouldn’t have had it anyway because it would have been on file with the hotel where I was staying.

I really didn’t care, though, because I’d already grown to hate Sofia and was ready to leave. The only thing that pissed me off about the exchange was that I had paid for my night’s lodging and I didn’t want to waste the money. It was the principal of the thing. I didn’t tell my inquisitors this, however.

At this point, the scam appeared to break down with all three conspirators jabbering at each other rapidly in Bulgarian. Voices rose, my passport was returned and the woman took my arm as she walked me away from the car.

As we walked off, she repeated her spiel. She was a friend of the men and she just happened to be in from Plovdiv to attend a beauty seminar. She also said she worked for a cosmetics company, magically produced a small bag from nowhere, held it up and told me she wanted me to have a bag full of free cosmetics as a gift. Before I could say anything she opened the bag and pulled out bottles of shampoo, shower gel for women, moisturizing cream for women, shaving cream (based on some of the people I’d seen my two days here I was sure that was for women, too) and crystals for soaking tired feet.

I knew where the conversation was headed but decided to play dumb just to be ornery.

“I’m confused. Does this mean I can stay?” I asked.

Looking at me pointedly, she said only, “Those men, they are friends of mine,” then paused, leaving the statement hanging in the air.

“My name is Lena and I’m from Plovdiv. I’m in town attending a beauty conference,” she said, repeating the entire story all over again, until she closed saying, “Due to a special offer today only I would like to give you a gift of free cosmetics for only 500 leva (approx. $3 US).”

I paid the stupidity tax with alacrity, thankful she and her friends weren’t more ambitious.

“How is your day going?” she asked.

“Pretty good,” I replied, nonchalantly.

“No, it’s not,” she responded.

This was news to me. Granted, I had spent most of my first day-and-a-half in Sofia getting lost. The street names, which were all written in Cyrillic, had changed so much since my guidebook’s map had been published that I spent most of my time looking for streets that no longer existed. I may have been agitated and ready to move on to another city, but I didn’t consider it a particularly bad day. And I figured I would have been the first to know.

The woman then informed me she just happened to be in town from Plovdiv for a beauty seminar sponsored by a cosmetics company. She also said she was a friend of the men who hadd detained me and that she would translate because she spoke better English. Then, the real fun began.

The first man looked at me, held up my passport and said in English, “You can’t stay.”

The woman then translated for him, saying, “You can’t stay.”

“Why not?” I asked, looking at the first man.

“He asked ‘why not?'” she said, in English, to the first man.

At this point I realized I was locked in a four-man Abbott and Costello routine and just strapped myself in for the ride. The gist of their argument was that I couldn’t stay in Bulgaria because I didn’t have a statistical card. I told them I didn’t have it because the border agents wouldn’t give me one even though I requested it. Looking back on it, the argument was pretty stupid because, if I understand the policy, if I had been given a card I wouldn’t have had it anyway because it would have been on file with the hotel where I was staying.

I really didn’t care, though, because I’d already grown to hate Sofia and was ready to leave. The only thing that pissed me off about the exchange was that I had paid for my night’s lodging and I didn’t want to waste the money. It was the principal of the thing. I didn’t tell my inquisitors this, however.

At this point, the scam appeared to break down with all three conspirators jabbering at each other rapidly in Bulgarian. Voices rose, my passport was returned and the woman took my arm as she walked me away from the car.

As we walked off, she repeated her spiel. She was a friend of the men and she just happened to be in from Plovdiv to attend a beauty seminar. She also said she worked for a cosmetics company, magically produced a small bag from nowhere, held it up and told me she wanted me to have a bag full of free cosmetics as a gift. Before I could say anything she opened the bag and pulled out bottles of shampoo, shower gel for women, moisturizing cream for women, shaving cream (based on some of the people I’d seen my two days here I was sure that was for women, too) and crystals for soaking tired feet.

I knew where the conversation was headed but decided to play dumb just to be ornery.

“I’m confused. Does this mean I can stay?” I asked.

Looking at me pointedly, she said only, “Those men, they are friends of mine,” then paused, leaving the statement hanging in the air.

“My name is Lena and I’m from Plovdiv. I’m in town attending a beauty conference,” she said, repeating the entire story all over again, until she closed saying, “Due to a special offer today only I would like to give you a gift of free cosmetics for only 500 leva (approx. $3 US).”

I paid the stupidity tax with alacrity, thankful she and her friends weren’t more ambitious.

It may have been my first shakedown, but not my last. Later in the day I was outside the Church of St. Petka Samardjiiska (which rhymes with Bamardjiiska) when I noticed a man standing beside a large, strange looking dog. As I got closer I realized the dog was a bear. Once the man saw me he began playing an odd stringed instrument and the bear got up on its hind legs to dance. Stunned, I could do nothing but stand and watch in shock as I saw a spectacle straight out of Ed Sullivan show reruns. Once the performance was over the man held out his hand for money and grunted. I didn’t know if this was a part of the act or not, but the man continued to grunt at me and pointed at my pocket.

I felt like I had just received a package some mail order company had sent to me even though I hadn’t ordered it. In the States, the package would have legally been mine and I wouldn’t have had to pay for it. I felt the same way about this situation. I hadn’t wanted the performance and hadn’t asked for it, but he gave it to me anyway. At face value, I owed him nothing. More practically speaking, I also had to consider that he was armed with a really big bear. The problem is I didn’t know how much to give the guy. My guidebooks covered many eventualities on when to tip waiters and how much to give a bellman, but none of the books say how much to give a man threatening you with a fully loaded bear.

Truth be told, the brains behind the operation wasn’t all that talented. All he had to do was play the tune, which he didn’t do that well. The bear was the one that had to dance and keep time to a song played by a man who couldn’t keep a beat. Bad old jokes aside, I couldn’t imagine a bear needing much money. After all, in my travels I had never seen a bear walking through a market with or without cash or a credit card. I would have been happy to run up the street to buy some Purina Bear Chow, but I didn’t know where a pet food store was and the animal’s owner wanted something more substantial. Guessing, I pulled out a handful of change and gave it to the man. Apparently it wasn’t enough, though, because the man grunted and the bear rose up on its hind legs. Frustrated, I threw more cash his way, but that still didn’t seem to satisfy him so I said I wasn’t going to give more, then ran for my life.

I can’t tell you how embarrassed my family would have been if I’d died that way. I can just see the conversation between my mom and the official calling to report my death.

MOM: How did he die?

OFFICIAL: He was mauled to death by a bear.

MOM: A bear? Where was he? A forest?

OFFICIAL: No, he was in the center of the city in front of a church.

Still, such a monumentally embarrassing call might be enough to erase the memory of the chagrin she felt when my elementary school principal called to say he found me snooping around in the girl’s bathroom in second grade.

Even though the bear didn’t chase me, I realized I’d had enough of Bulgaria and wanted to leave. Quickly.

There was one roadblock to my rapid departure, though: I had too much money.

For the second time in the trip, I had my money tied up in a non-convertible currency. The first time was in Lithuania when I changed a $100 Travelers cheques a day before I left the country, not knowing that there was only one town in Poland that would exchange lit for zloty, and that was at the border. I didn’t discover the problem until I reached Gdansk on the opposite side of the country and ended up without money for a day. As a result, I had to spend a day traveling back to the town just so I wouldn’t lose $70 US. Although I didn’t know about the convertibility issue the first time, I was well aware of it in Bulgaria. I knew the economy was in such a shambles that no other country would accept Leva. I also knew Bulgaria had an official policy allowing travelers to exchange foreign currency for Leva, but wouldn’t let moneychangers buy it back. I didn’t want to cash in a $100 traveler’s cheque, but I had no choice. I was out of $20s and $50s.

Rather than lose it all, I tried to spend it.

Easier said than done. I couldn’t buy anything big because there was no room in my backpack. I couldn’t purchase anything expensive out of fear it might be stolen. I didn’t need film or batteries and I couldn’t find any books in English, so food was my only option. My temporary roommate (a fellow traveler who helped me find lodging in a room in a Bulgarian woman’s flat) and I decided to throw our money around. We went to a pizza place that was spendier than the restaurants that surrounded it, bought our own pies, individual salads, pitchers of our favorite beverages and large desserts. When we were through our bills came to a whopping $5. Even after I bought a ticket to Istanbul and snacks, I still had $30. Fortunately, the room finding service that referred us to the Bulgarian lady agreed to buy back the money at a reduced rate.

Now all I had to do was tell the lady I was leaving. No easy task. The woman who was so short her head barely reached my armpit didn’t understand English. In fact, she only knew two broken English phrases that I could understand and I heard them when I checked in and told her I was from America. She imitated “The Fonze” from “Happy Days,” gave a thumbs up and said, “Americanski, Aaaaay. Communiski, Kaput,” turning thumbs down on the last two words. I’m still not sure how I did it because my roommate, who spoke some Bulgarian wasn’t with me. I’m sure I must have used one of the English phrases that everybody understands like “Finish,” “I go,” or something like that.

Rather than throw away the free cosmetics I’d bought, I kept the aftershave for myself and gave the rest to my hostess. She was so excited she hugged and kissed me and prattled on and on for quite some time, and I didn’t understand a single word she said.

But at least she was happy. I hope it didn’t turn her skin green.