The Place is Lousy With Jews

“Organized religion will be the death of civilization as we know it.”

–Mark Twain

“That’s why I like Judaism so much. I can’t think of a less organized religion.”

–Yours truly on Jews and Jewishness

I never should have visited Jane Wolf.

Or, I should have only spent an hour with her, not three nights on her couch. Because that’s where the end began, even though I still had two months to go.

It was bad enough I was burned out on the Jewish part of the trip, but visiting her added a dose of homesickness. Nothing terrible happened there. It’s just that once I saw someone I associated with Seattle, my heart began wondering when I was going to the Honey Bear Bakery, stop by the B’nai B’rith Hillel House or go to an author reading at Elliott Bay Books, all favorite hangouts back home. Intellectually, I knew all those things were two months and thousands of miles away, but I couldn’t convince my heart.

Don’t get me wrong. I enjoyed Budapest. It’s just that I got lazy and wasn’t willing to venture too far from the tourist path. There were times I wasn’t willing to hit even those well-worn paths. I didn’t realize this until I wanted to leave the city and didn’t know where to go.

Unfortunately, it happened when I’d finally reached a city with a thriving Jewish population. Although there were more than 80,000 Jews living there and at least 23 synagogues still in use, I couldn’t have cared less. Even more ironic, I probably would have had better luck tracking my family’s history here because my mom’s relatives had lived in Buda and Pest (the two cities merged with Obuda to form Budapest) and there were more people still alive on her side of the family who might have known something about them. Unfortunately, I was interested in my father’s side of the family and hadn’t considered the alternative.

That was my other mistake.

Although I hate to admit it, I probably wouldn’t have even visited the Jewish district if Betsy hadn’t loaned me her Frommer’s Guide with walking tours of the city.

Unlike many of the other Eastern European cities I visited, there was still plenty to see in Budapest’s Jewish section, not far from the main downtown shopping area. I didn’t need to look any further than “The Face of Jewish Budapest” walking tour in Frommer’s to see how much. The book predicted it would take three hours to see it all and it was right on the money (which is three times longer than it would have taken to see the Jewish section in most places I visited). The tour featured stops at The Jewish Museum, the Great Synagogue, described as one of the largest in Europe. Although the Great Synagogue was undergoing renovation and surrounded by scaffolding, its beauty was still apparent. Other places included the Old Orthodox Synagogue, the restaurant next to it, a nearby square, a salami factory, attached courtyards and a cheap Jewish restaurant where a guy hustled me to change dollars to Forint and then got quite upset when I didn’t realize he was talking to me even though he was speaking Hungarian.

There was also a bizarre sculpture memorializing Raoul Wallenberg, the diplomat who saved numerous Jews from the Nazis by issuing forged papers. At least that’s what the book says the sculpture memorializes, but the creation itself looks like a man flat on his back looking at an angel emerging from a nearby apartment building. I don’t know about you, but if I saw a big angel emerging from the bricks of a third story flat, I’d probably be on my back, too, and I wouldn’t be thinking of some diplomat.

The main reason the community is so large is that the Germans didn’t take Hungary until 1944, and didn’t have enough time to complete their mission. Even so, they still had a huge impact on the country’s Jewish population. In 1941, there were more than 800,000 Jews in all of Hungary. Three years later more than 440,000 Jews outside of Budapest were sent to Auschwitz. In addition, Budapest’s 2,000 Jews were rounded up and put into ghettos with many eventually being deported to Auschwitz. By the time the war was over, more than 550,000 Jews were killed.

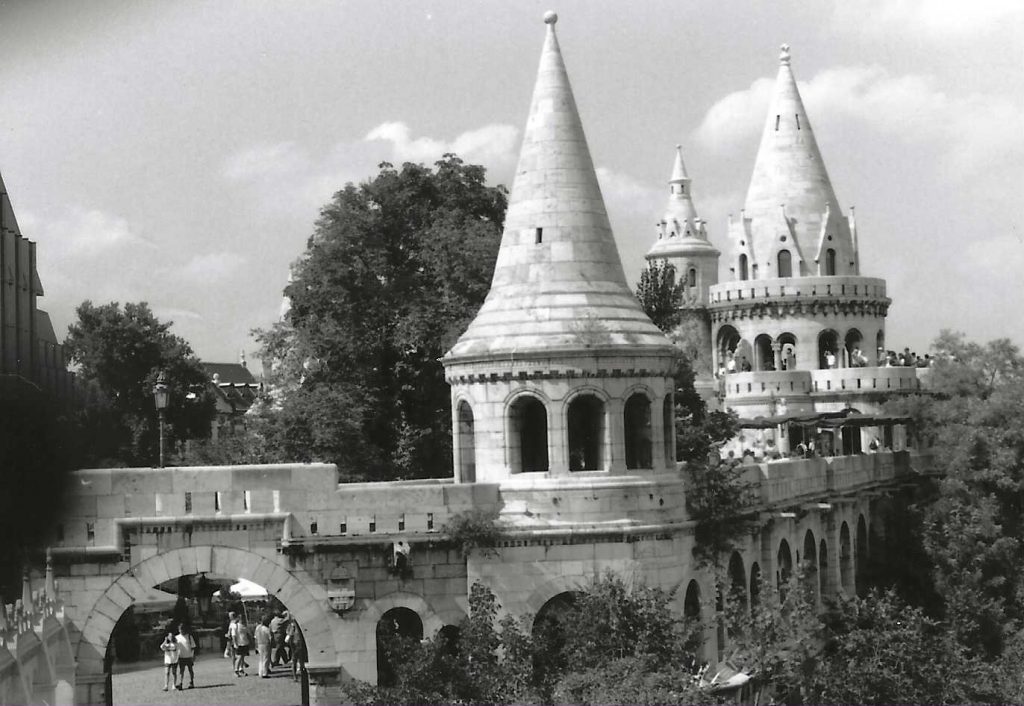

Once my day tour of the Jewish district was over, my mission to trace the sad history of the Jews was, too. It was too much for me. I decided I couldn’t take it anymore and spent the next day in the Castle District. I didn’t follow the guidebook, though, because it said the route took four hours and I didn’t want to commit myself to such a large time chunk. Instead, I wandered aimlessly through the historic district on the west side of the Danube River known as Castle Hill. To paraphrase Yogi Berra, “The place is just loaded with atmosphere.”

The Castle District is the type of place people refer to when they say, “If you can only see one thing while you’re here, then you must see….” The kilometer -long limestone plateau is home to the city’s most important monuments from the Royal Palace and National Archives to museums covering almost every discipline including music, pharmacy, baking, catering, the military and telephony. Tired as I was, I still felt a sense of history as I ambled the district’s four major stone streets, snuck down side streets and peered into courtyards of buildings in a place once considered to be home to commoners. The current residents are anything but. Although I enjoyed skulking around the aging courtyards, my favorite place is Magdalene Tower, which was once part of a church and a mosque, but now represents all that was left standing after a wartime bombing. To call it cool doesn’t do justice to the unattached tower.

The remnants of magdalene cathedral bombed out in world war II. If you look close, you’ll notice that tower isn’t attached to the building behind it.

Jane Wolf and I may not have been best friends in Seattle, but we knew each other through B’nai B’rith Hillel, the University of Washington’s Jewish student union. We had the same friends, went to the same parties and played on the same softball team. Despite that, Jane and her boyfriend were more than a port in a storm. They were friendly faces in an anonymous world where it wasn’t always easy to find someone to talk to, especially about issues like the Holocaust and the sad history of the Jews in Eastern Europe. It wasn’t the same as traveling with a girlfriend, but it was still good to talk to someone.

I wasn’t sure how Jane had gone from receiving a graduate degree in public policy at the UW to working for an environmental organization in Hungary, but I didn’t really care. I was just happy to sleep on her sofa and do laundry without waiting in line for washers and dryers behind four or five other youth hostelers.

Seeing her for the first time in a year was oddly anti-climactic. Although hers was the first friendly face I’d seen in months, not much had changed. She was still the same diminutive woman I remembered, only her hair was different and she was more domestically-oriented as evidenced by making baba ghanouj and vegetable sausage as well as puttering around while we talked. Our conversation was a bit stilted due to the difference in our lives. Although I thought we were both in transitory phases, I was wrong. While I felt like a temporary vagabond, she was Martha Stewart lite, all the great tips without the nasty attitude. The clash of cultures made me feel like I was the single guy trying to communicate with someone in the land of the married.

I’m not saying this to impugn her hosting skills. She was the consummate hostess.

A visit from Jane’s friend and neighbor, Nicky, helped liven things up just as Jane finished dinner preparations. A freelance writer, Nicky stopped by to call an editor in the States because her phone wasn’t working and stayed for supper. We all exchanged travel horror stories until talk turned to my next destination.

I was so aimless I didn’t know what to say. I didn’t even have a destination in mind until Nicky mentioned that Bosnia was now safe to visit.

Spoken like a true journalist.

I didn’t start aspiring to go to Bosnia-Herzegovina. After all, I’ve always regarded travelers who got stuck behind battle lines in world hot spots to be just plain stupid. Hostilities don’t break out overnight. Although I can’t speak from personal experience, there always seems to be plenty of warning if people are paying attention to little clues: travel advisories, anti-foreigner rallies, the evacuation of consular officials and their dependents. Consequently, I’ve always thought the people who got caught in the crossfire were, at best, asking for trouble and, at worst, asking to be killed.

At the same time, however, I’ve taken joy in doing things that shock my family. Nothing as dangerous as going into battle zones, mind you. Just taking calculated risks and doing things my sedentary family would never dream of — jumping out of airplanes, climbing on sheets of ice, traveling around the world for a year for no particular reason — so I figured the next best way to rattle my relatives would be to send them a postcard that said something like, “Greetings from sunny Bosnia”, never mention the card and see what reaction I got.

Once Niko said she’d visited a place I’d grown accustomed to seeing in newspaper stories preceded by the phrase “war-torn,” I was intrigued. I was seriously considering going until I researched logistics. Although I didn’t list my profession, consulate staffers refused to believe me when I said I wasn’t a journalist. When I told them I was just a tourist going to Bosnia on holiday, the bureaucrat on the other end of the phone line laughed and hung up.

I was also surprised it was difficult to get transportation there. Trains were non-existent, the roads were rough, there was only one bus going to Sarajevo each day and I couldn’t figure out why. Until I remembered a minor detail: IT WAS A WAR ZONE. (Technically, that was not true. By August 1996, hostilities had ceased, giving way to unsanctioned random acts of unkindness and senseless acts of ugliness.)

Ruling out Bosnia only made things worse because it left me with no destination. None of the alternatives did much for me, either. Rumania had Transylvania, but I heard the country wasn’t all that nice and visas were expensive and hard to get. Slovenia had escaped the fighting plaguing most of Yugoslavia, but it was in the wrong direction if I wanted to reach Israel and still have time to work on a kibbutz before returning home for my sister’s wedding. Croatia was too expensive. Yugoslavia had cheap visas, but I wasn’t all that interested. The only place left was Bulgaria and the capitol city, which I had always associated with Nation Public Radio’s Sylvia Pojoli. I still had to get a Yugoslavian visa but my guidebook told me transport visas were free, so I wasn’t worried. I figured I had plenty of time.

I was wrong on both counts.

The visa wasn’t free and I had less time than I thought. I spent an afternoon waiting in line to get into the visa office and when I got there, the clerk told me there was a $20US charge for a visa, and local currency wasn’t acceptable. I got this piece of news 11 minutes before the embassy closed and the nearest money exchange place that I’d seen was 10-minutes away. This wouldn’t have been enough to worry me, but not having the money meant I’d have to waste another morning in line. In addition, if I didn’t get in it meant I would be stuck in Budapest for four more days because all official buildings were closing in observance of the city’s 1,100th birthday.

A younger me would have stuck around to experience a multi-centenary celebration. After all, when I was 20 years younger, I made my parents drive all over Dallas in search of the ultimate Bicentennial celebration on July 4, 1976 even though we were from out of town, didn’t know the city and got hopelessly lost every time we got off the freeway. Of course, I was younger then, more enthusiastic and I didn’t have to do all the driving myself. Now, I was old and bitter and in a hurry to get back on the road so I could finally get off the road and I just didn’t care.

I was one of the last people to get a Yugoslavian visa before the office closed for the next thousand years.

Ben Franklin was right. Fish and guests do stink after three days. I learned this lesson the hard way when a friend who was supposed to stay at my house for a week and travel around the Northwest looking for a job stayed two weeks. By the time he left, I never wanted to see him again, and still haven’t. That’s why I promised myself I would only stay with Betsy for three days. Once I started to drift and couldn’t decide where to go, I moved to a youth hostel downtown. Leaving Jane’s made me feel lonelier than I’d felt all trip, except on that unbearably hot morning I woke up in Djakarta many months before.

The only thing that kept me going was my reporter’s instinct. I didn’t really want to do anything, but I got sucked into researching a story about the Jews of Budapest when Betsy introduced me to a Jewish Fulbright Scholar from the States who had become an expert on the community. She told me she could find English-speaking Hungarian Jews who would do interviews, and got me to attend services at conservative and orthodox synagogues.

Although I never met any locals at either place, I did meet two nice women from the States at Friday night services and we went to dinner at an outdoor restaurant overlooking the Danube. Once seated, we waited a half-hour for a menu and just as long to get served. Suave and debonair world traveler that I am, I tried to attract the attention of a waiter and ended up catching the attention of a band of musicians roaming through the restaurant in search of tips. When our waiter finally showed up, he was quite personable and funny and later advised us which deserts to order and which to avoid, giving the impression that if he hadn’t approved of our selection, he wouldn’t have written it down. We all ordered crepes, which he approved of, but he had a problem preparing the dish because the wind kept him from lighting the flambé.

The meal ended on a happy note, but I wasn’t so happy when I got back to the hostel and realized it was after midnight. I still had to get up early in the morning and meet Jane’s friend by 7:45 a.m.

Feeling lonely the next morning as I walked to synagogue, I stopped, called Gena and unintentionally got revenge on the woman who dumped me in Australia. Gena was having a Shabbat potluck dinner and many of the people who go to Hillel were there because the Jewish student union didn’t hold services in summer. When the assembled crowd heard I was calling, they yelled greetings as I spoke to the woman who was watching all my worldly stuff. When I asked who was there, she counted off the names of many friends including someone named Janna I’d never heard of.

“Janna? Janna who?” I yelled into the phone.

“What do you mean Janna who?” Gena yelled back.

Considering Janna had sent me a letter in Warsaw to tell me she had broken up with the guy she was dating, I’m sure she wanted to talk to me, but I didn’t have time. My misunderstanding was unintentional, but there was silence at the other end of the line when I didn’t immediately know who Gena was talking about. I know I should have been a better man and apologized or said something, but I knew my silence spoke volumes and I was still so irritated that I didn’t feel generous enough to let my ex off the hook.

My morning at the orthodox synagogue reminded me of a strange custom I’d noticed at shuls throughout Eastern Europe: prayer by hanging out. It has many different variations, but some things never change. The rabbi always stands at the altar in the center of the synagogue chanting prayers as a smattering of the congregants appear lost in fervent prayer, bowing back and forth as they read. At the same time, however, many of the men in attendance stand on the sides of the synagogue holding open prayer books as they shake hands and chat. I don’t know whether this means that most of the men who attend morning services are former class clowns or just the guys who sat at the back of the room and talked with friends because they didn’t know what was going on. Or, maybe they know what’s going on, they’re bored, have nothing else to do and are trying to get the latest soccer scores. I’ve never been able to find anyone who can answer my questions about the practice.

Going to orthodox synagogues on the road also taught me how little I know about Judaism. I can read Hebrew, but can’t translate it. When I was in the States, New Zealand or Australia my functional illiteracy never bothered me because I could always look on the opposite page for an English translation. Eastern European prayer books also have translations, but not in English. My knowledge of Hebrew allowed me to keep up in the first few countries, but the more time I spent in synagogues, the more distracted I became. So, I started meditating during services in an attempt to stay awake. By now, however, I gave up all pretense of even meditating. Instead, I smuggled in my LP Eastern Europe book and stuck a prayer book in front of it. As a result, I didn’t worry about falling asleep, I looked like I was praying intently and I got a chance to plan the next week of the trip.

Much to my frustration, Jane’s friend was only partly right about meeting English speakers. I met many of them at lunch after the service was over. Unfortunately, most were Israeli, not Hungarian. This meant I’d spent two extra days in Budapest when I could’ve been on my way to my next stop and several countries closer to a kibbutz where I planned to close out the trip.

Suddenly, my mind began unraveling under the pressure of attempting to reach Israel in enough time so that I could work on a kibbutz for two months (the minimum commitment allowable) and still get to my sister’s wedding. A trip this big really shouldn’t be rushed and I was doing exactly that. It had finally caught up with me.

Worry over my sister’s wedding also inspired thoughts of my mortality. This trip was supposed to be my last hurrah as a single guy. I had it all planned out. My (now former) girlfriend was going to meet my family at the wedding, I was going to spend Thanksgiving with her family, then we were going to get married and live happily ever after. Those dreams ended when I got a “Dear John” letter in Adelaide. Sure, my friends were telling me we could get back together when I got home, but I wasn’t sure I wanted to be with someone so thoughtless. At the same time, I began wondering if I’d ever find the right woman. It was as if my biological radio alarm clock had gone off with the screeching sound set on full accompanied by the radio playing “Ana Goda Dovida” at top volume. With time running short, the walls closing in and no one to talk to, I began to worry that I would die alone.

“I don’t want to die alone,” I cried plaintively to myself…

Then, I heard the stand-up comic side of my head fill with sinister laughter and say, “I want to take somebody with me.”

The more I thought about it, the more depressed I felt, fearing I might never be able to come in from the cold. The worse I felt, the more I needed to reach out to someone. And that someone was Donna. When I realized I was at a pay phone only what remained of an extremely shallow pool of willpower gave me the strength to call my friend Michael instead and we talked until the crisis passed. The conversation wasn’t enough to keep me from feeling alone, though.

Still feeling desolate, I called my older sister just to say hello. This was not the right answer, either. All she wanted to do was tell me about all the wonderful things her two year-old daughter had done and how her two-month old was doing. Potty training and kids saying and doing the darnedest things were the last things I wanted to hear. Before I could get a word in, she put her two-year-old on the phone to talk to me, long distance, at an astronomical cost. It took me several minutes to get her back on the phone and by then I was too tired to even bother.

As I hung up and walked away, the comedian in me responded by saying, “Uh, Dave, you’re a guy. Guys don’t have biological clocks.”

It didn’t help.