Everyone Gets Tired

”I’m so tired, I’m feeling so upset,

Although I’m so tired, I’ll have another cigarette,

And curse Sir Walter Raleigh,

He was such a stupid git.”

— From “The White Album” by The Beatles.

Everyone is tired. The novelty of having a relative or friend on the road calling from unusual, exotic locations had worn off and there were starting to be days when I wondered when I was going to go back home and get the trip over with.

By the time I arrived in Vilnius, Lithuania at 5 a.m. with nowhere to go I realized five months is a really long time to be traveling. Looking back on the 150 or so odd days before I arrived in Lithuania’s capitol, though, they were the blink of an eye. It was difficult for me to believe that last month at the same time I had been in Hong Kong, and months before that in Saigon, Singapore, Australia and New Zealand.

By this point the only thing keeping me going was dedication to my mission and a fading sense of wonderment. I wanted to see the places my family came from even if I didn’t know their old addresses, I wanted to know if any were still alive. By now I would have given anything to see a familiar face or a family member I didn’t know I had that spoke English so I could sleep on a nice bed or cook for myself, veg out and watch television until I fell asleep.

Oddly, I didn’t even know I’d felt this way until I began writing in my journal. I knew my feet were hurting sooner and drowsiness was setting in earlier than before. I had initially attributed it to my pushing myself to update my journal after falling behind by two weeks, but I finally saw there was more to it. I no longer had the spring in the step that I used to have and my allergies had returned with a vengeance.

It’s not that I wasn’t enjoying myself. It’s just that my smiles from genuine excitement and contentment didn’t come as often, but they still came. I also had to push myself to leave my hotel and research the city’s Jewish community, and this was only the second week of my search. I desperately needed a travel companion who I could talk to about what I had already seen, but my close friend Katy Koenen wasn’t a backpacker and my former girlfriend was too busy looking for a job to leave the country.

So, I decided to take a week off and go at a relaxed pace.

Taking time off from hard travel should be relaxing. I believed that taking a vacation from my vacation would be fun, peaceful and trouble-free. Instead, it was just plain odd.

It all started shortly after I arrived. I was walking the streets looking for a place to stay and met a Hong Kong Chinese man from London who asked if we could combine forces to look for a room. To say he looked out of place in a city filled with Eastern European faces is an understatement, but he knew his way around strange cities even better than me. When I located a promising prospect in my guidebook he found before I could locate it on my map. Part of his prowess undoubtedly stemmed from the fact that this tall, thin, 38 year-old had spent many years traveling the world plying his craft: Teaching salsa dancing.

“I was quite popular in Spain,” he told me.

Even now I don’t know if he was kidding or serious.

We found a double room with fridge, sink and stove for $4 a person. Not bad for two guys who didn’t know each other’s names.

No matter how many times this happened on the road, I was still amazed by a backpacker that allowed complete strangers one minute to trust each other with all that they own the next. I knew one day I’d probably regret that misplaced trust, but it didn’t happen while we roomed together. At least, he didn’t con me out of money or personal possessions. Instead, he stole my personal time even if only in the nicest way.

No matter where Bo went, he insisted I go–even if he was so pleasant I didn’t notice.

As a result, I spent most of my first two days trying to score free lodging with international students at the University and watching Bo scam on women half his age. At one point he was so taken with a 19 year-old girl in town for a University entrance exam he convinced her and her friend to hang out with us. The catch was I would have to keep her slightly less attractive friend entertained even though she spoke little English. Although we had difficulty communicating, I realized Bo sold her short; because she was far more animated when she spoke and had a glimmer in her eye that showed she was capable of stirring trouble, given half a chance.) She was far more attractive.

His attempts to score failed miserably. His efforts to find a dorm room were similarly unsuccessful because the students were so poor they had little to share. Fortunately, a student who thought he was an American Indian (and constantly asked his opinion of Carlos Castenada) surprised him by finding a room big enough for two. Ever the nice guy, Bo invited me to join him, but I wasn’t quite as enthusiastic about leaving a cheap room downtown for a dorm room 40 minutes away from downtown. Granted, my staying meant I had to pay double for my room, but it also meant I would be Bo-free for the rest of my stay.

Vilnius looked healthy, but all it took was a little poking around to find things weren’t as prosperous as they seemed. Buildings scattered throughout the city looked like they were still burned out from World War II, grocery store shelves appeared full, but only because store owners took up as much shelf space with each item as possible. Consequently, bags of the same type of candy would be laid side by side to take up space where in the U.S. there would be so many different items in stock there wouldn’t be enough room to stack bags atop one another.

Vilnius looked healthy, but all it took was a little poking around to find things weren’t as prosperous as they seemed. Buildings scattered throughout the city looked like they were still burned out from World War II, grocery store shelves appeared full, but only because store owners took up as much shelf space with each item as possible. Consequently, bags of the same type of candy would be laid side by side to take up space where in the U.S. there would be so many different items in stock there wouldn’t be enough room to stack bags atop one another.

A man I met in a restaurant told me he was a representative of the Danish government (strangely enough, I never met anyone from the Donut government) in Lithuania to help set up a dairy farmer’s cooperative. Greedy officials in the Lithuanian ministry overseeing the project were scuttling the deal because they weren’t getting enough graft, he said. A second generation American-Litvak York who had returned to his homeland and had taken a job as a government interpreter had more chilling news. It had already been a bad year because a bank merger turned failed unexpectedly, wiping out the life savings of many customers, but it was going to get worse because the government was so deep in debt there wasn’t enough heating oil available to help the country weather Eastern Europe’s brutal winter.

The more I talked to people, the more depressed I became. Fortunately, many people who could speak English were too reserved to talk to me and the rest couldn’t. The language gap made me feel more isolated, which further depressed me. Out of frustration I stopped talking and just poked around the city.

My hotel was perfectly located for the type of sightseeing I like: aimless wandering. Not only was it across the street from a bombed out building with Hebrew lettering on the inside walls, it was a block away from a synagogue and a three minute walk to the Old City. Already gun-shy due to the aloof populace, I opted against taking my chances with the city’s Jews and roamed the Old City. There was plenty to see thanks to a folk festival and a wide range of interesting buildings such as Vilnius Castle and Cathedral Square as well as plenty of tiny, twisty side streets. I spent two days wandering those streets in a state of perpetual discombobulation. Along the way I stumbled across a daily street market, a great bakery, parts of the university, and a few unexpectedly amusing design features above shop doors that didn’t seem to fit a city with such humorless people. My favorite was a pair of arms holding a plate filled with pancakes. The arms were stationed over the transom of a breakfast café’s door.

Two of my biggest miscommunications in Eastern Europe took place here, with one occurring in the cafe when Bo and I ate lunch. All I wanted was a cutlet so I went to the counter and ordered kotleta (Lithuanian for “fried mystery meat”). In response, the waitress pointed toward the bathroom attendant who took my money. I thought it was odd, but I didn’t speak Lithuanian so I went with it. I got suspicious when I pulled some money out of my pocket and was looking for more when she told me I was paying too much.

As it turns out, the waitress misunderstood my order. I said “kotleta,” but she thought I said, “toileta” so she dispatched the bathroom attendant to take my money.

We all had a couple of good yucks over that one.

The person on the other end of the second miscommunication wasn’t as amused, however.

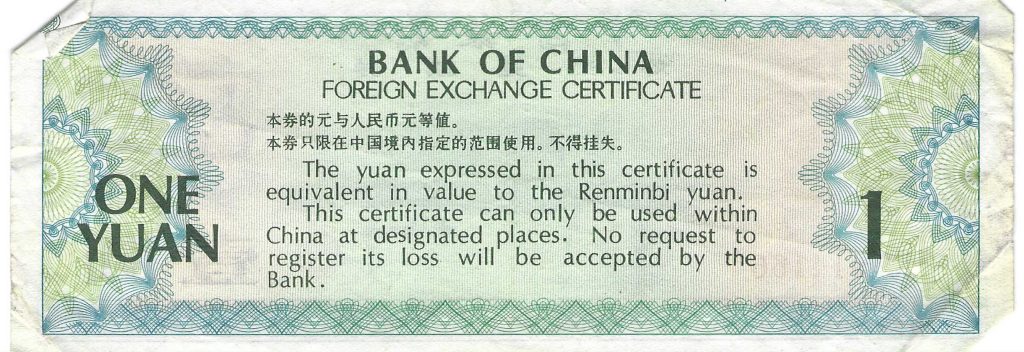

The snafu occurred at a ticket kiosk when I went to buy a bus ticket. I reached into my pocket, pulled out a 10 and had a clerk refuse to accept it. I took her refusal as just sheer rudeness and possibly slightly discriminatory. Just as I was about to create a scene, however, I realized I’d given her a 10 Yuan bill from China, not a 10 Lit note. So I reached into my money belt, pulled out another 10 and waited for my ticket.

And she refused again.

I’ll be damned if I hadn’t paid with another 10-Yuan note.

She was not amused.

My luck communicating with fellow English-speakers wasn’t much better. After spending two days hanging out with a married couple from America who were quite successful in their freelance travel writing careers, I asked them for the secret of their success. After all, I reasoned, you don’t survive 46 years in the business and publish a few books without doing something right.

Their response was short and to the point.

“You should do a story on your trip,” the husband said.

Really? How brilliant! After eight years freelancing, lord knows I never would have come up with that on my own. Gee, could you be a little more specific, I said, facetiously.

Really? How brilliant! After eight years freelancing, lord knows I never would have come up with that on my own. Gee, could you be a little more specific, I said, facetiously.

Really? How brilliant! After eight years freelancing, lord knows I never would have come up with that on my own. Gee, could you be a little more specific, I said, facetiously.

He then gave me a can of SPAM and a can of tuna.

As much as I enjoyed my walkabout through Senamiestis (the old city), all it took to shock me back into returning to the mission at hand — seeking out Jewish Latvia — was stumbling across a plaque with a Star of David, some Hebrew, some Yiddish and the inscription “1941-1943 Vilniaus Geto Kankiniu Ip Kovotoju Atminmui.” It was the first of three memorials to a ghetto that covered all of the Old City. The marker surprised me because I expected Vilnius to be as devoid of memorials as Riga. In fact, the opposite was true. Where there were few Holocaust memorials and only a small museum recalling the infamy in Latvia, there was a whole building dedicated to the sad history of the Jews here plus two large rooms at a Jewish community center blocks away.

The number of memorials shouldn’t have surprised me. Before World War II the city was the center of intellectual Jewish thought outside of Palestine. Jews made up half of the city’s population and there were more than 100 synagogues in the old city alone. As the story goes, Judaism’s holy rollers wanted to open the late 19th century equivalent of a religious think tank, but weren’t sure where to locate. They received invitations from Brooklyn, a city in the Middle East and Vilnius. They chose Lithuania’s capitol city.

It reminds me of a scene from the end of “Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade.” When confronted with a room filled with possible Holy Grails a Nazi anthropologist-turned-fortune hunter grabs the closest, prettiest one, dunks it in a font filled with holy water and drinks deeply. Instead of gaining immortality, he is reduced to dust in seconds.

Without missing a beat the man who has been guarding the grail for a millenium earnestly weighs in with his opinion.

“He chose…poorly.”

Apparently, the scholars chose just as poorly.

I’m still puzzled they and their brethren throughout Eastern Europe couldn’t see it coming. On one hand, I can see that the killings were on such a grand and ordered scale no one could have imagined it, despite Turkey’s bloody massacre of thousands of Armenians at the turn of the century. On the other hand, I’m still puzzled that the Jews couldn’t see that years of pogroms were leading to this. Considering that Hitler had laid out his blueprints for a master race in Mein Kampf it wasn’t like the Nazis hid what they were about. In two short years the Jewish population of Vilnius went from more than 70,000 to 800.

The sheer number alone was hard for me to picture until I visited Panerai, a forested area on the edge of the city where the Nazis killed more than 100,000 Jews and Communists and buried them in pits. I was rendered speechless as I walked from one round mass grave to another, each one deeper than the last until I finally got to the largest, which had been dug up and left such a large crater that it was easily twice as deep as I am tall and 20 feet across. The thought of the number of bodies it would take to fill a hole this mind-numbingly big numbed chilled my bones even in mid-July. Man’s capacity for inhumanity still amazes me. Perhaps it’s a good thing I still have the ability to be shocked after all the killings I’ve seen on prime time television and movies and books about the Holocaust.

The sheer number alone was hard for me to picture until I visited Panerai, a forested area on the edge of the city where the Nazis killed more than 100,000 Jews and Communists and buried them in pits. I was rendered speechless as I walked from one round mass grave to another, each one deeper than the last until I finally got to the largest, which had been dug up and left such a large crater that it was easily twice as deep as I am tall and 20 feet across. The thought of the number of bodies it would take to fill a hole this mind-numbingly big numbed chilled my bones even in mid-July. Man’s capacity for inhumanity still amazes me. Perhaps it’s a good thing I still have the ability to be shocked after all the killings I’ve seen on prime time television and movies and books about the Holocaust.

The more I thought about what had happened there, the more uncomfortable I became with my decision to go alone. After all, I was the only person in an eerie forest on a remote edge of town Hell, even the museum that was supposed to be open was closed.

I couldn’t leave fast enough.

The Jewish cemetery was just as eerie. It was located in a populated area and there were people there when I arrived late in the day, but the lack of stones dating back before the 1950’s made the Jews seem a people without a history. As with Riga, none of the memorials date back to the 19th century because Nazis and their collaborators destroyed the cemeteries. In addition, the Communists took care of what the Germans missed, using markers as paving stones and building a football stadium at another.

While I didn’t find the name of any family members on the stones I could read, I did learn how the large pictures were being put on the gravestones. The photos weren’t being scanned in using some sort of computer technology. Instead, they were being pounded in using a chisel and a number of sharp pinpoints. The craftsman told me the varying size of the points allowed him to do everything from backgrounds to the fine detail work found in the eyes and teeth. His work was so good it was hard for me to tell that it wasn’t a photo. Amazing.

What made the visit to the cemetery even stranger was the difficulty I had leaving the area. I fell asleep on the bus back to the old city and woke up near the cemetery. It didn’t bother me; I figured I could ride the circuit again, but the driver kicked everyone off at the end of the line, near where I’d originally caught the bus. So I bought another ticket, waited an hour and gave the passengers a good laugh at my expense.

As I rode back and considered what I’d seen, I was genuinely boggled that the Nazis thought they could get away with such barbarism. It bothered me even more that they almost did. What made it harder was knowing that Latvian and Lithuanians were worse than the Nazis they tried to curry favor with. In Latvia, locals beat defenseless Jews entering the ghetto just out of sheer meanness. And here in Vilnius crowds cheered as a young boy beat Jewish people to death in the street in broad daylight.

Who knows?

Maybe the land does have a soul.

Maybe that’s why the Baltic States have suffered so many misfortunes since the War. The only problem with the theory is if that theory were correct, Germany would still be in shambles instead of an economic powerhouse. Of course, there are some people who would say Eastern Berlin still hasn’t recovered.

No matter how I look at the tragic past and the painful present of the Jews in Lithuania, I discovered that one fact remains incontrovertible: One of Europe’s great Jewish communities is breathing its last. The old people who know all about Judaism are dying, their children know little and their grandchildren even less. And they are leaving in droves.

Of the Jewish teenagers I spoke with, only one said she would stay and only because her parents didn’t want her to leave. She will likely change her mind when she graduates college and is unable to find a job at home.

In the interim, the Jewish community staggers along, giving it the old college try and doing its best to keep going. This, even though, officials realize the effort is pointless. The social and religious components were so far apart it seemed the two would never reunite. Sure, the teenagers meet at the community center on Fridays and one other day a week and they do discuss religion on occasion, but mostly they just hang out and do what teenagers do: mark time until high school graduation when they can get out while the getting is good. Just like small town teenagers throughout America. The key difference is rural kids leave home because they want to. Lithuanian Jews leave because they have to.

My visit left me with the feeling that the city of Vilnius had become a home to museum Judaism while Riga had managed to remain alive with few memorials. Although there aren’t many memorials to the Holocaust in Latvia, the community seems organized and vital. Meanwhile, the city the Jews called Vilna is littered with memorials of what was and never will be again. I’m not saying you must forget the past to survive, it just seems that the backbone of Jewish Vilnius has collapsed under the weight of its own heritage as Riga’s community keeps on keeping on.

The greatest irony of all, however, is that Operation Exodus and more open emmigration policies were accomplishing what Hitler couldn’t. While he couldn’t wipe out all of Europe’s Jews, the modern day immigration efforts appear to be doing just that, even if it is relocating Jews, not killing them.

It was a depressing thought on which to end another long day in Vilnius.

Unable to take any more, I called it quits and went to bed around 8 p.m. only to be woken at 6 a.m. when the hotel manager pounded on the door to tell me she had brought my friends — three big backpackers she wanted to shoehorn into a room that would be a tight fit for three. It didn’t improve my outlook at all when she told me she would charge me double if I didn’t agree. Maybe it was fate’s way of telling me it was time to move on.