The Light at the End of the Tunnel…Goes Completely Out

“It’s always darkest…. before the light goes completely out.”

–Seen on a bathroom wall at the University of Missouri

Ever since I first heard Douglas Adams’ book title, “The Long, Dark Teatime of the Soul,” it amused me. I never understood what it meant until I experienced it myself.

Although I’d been tracing the tragic history of the Jews — and my family’s place in it — for only a month, it was taking its toll, despite my best efforts to escape every few days. Sadly, it’s hard to escape the reality of pogroms, unmarked ghettos, mass graves, headstones as paving stones, destruction of cemeteries and, the final insult for people who survived seeing their history being taken away: torture, overwork, deprivation and death.

What made it worse was knowing that even though Hitler was gone, one of his goals was still being realized: the decimation of Eastern Europe’s Jewish community. Russia picked up where the Nazis left off, persecuting Jews and forbidding religious practices so that the few Jews who wanted to practice their religion couldn’t. In addition, people in succeeding generations were so tired of persecution for being born into a faith they knew nothing about that they wanted nothing to do with something that had brought them so much grief when they finally got religious freedom. Others, who were interested in returning to their roots, didn’t know how to practice, and those who did were dying off. Plus, their kids didn’t want to stick around because there’s just no opportunity.

As much as I hate to say it, the international Jewish community may be putting the final nails in the coffin of Eastern European Jewry with Operation Exodus. The effort to rescue Jews had been siphoning away the best and brightest members of the population including doctors and scientists, leaving only people who feel they’re too old to start all over again. Sure, the younger set would have left anyway, but that didn’t make it easier to like what I was seeing.

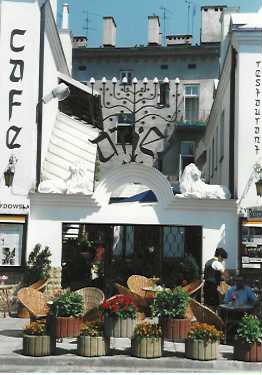

Consequently, I was thrilled when I finally found Kazimierz, Krakow’s Jewish quarter. There, my culture was so alive that there are five Jewish restaurants within one block — one kosher, three with nightly Jewish concerts — a Jewish museum (in an old synagogue), the city’s old Jewish cemetery and the Center for the Study of Jewish Culture. It almost made me cry. Tears welled up in my eyes when I walked into restaurants and shops filled with Judaica ranging from books and mezuzahs to paintings, pictures and hand carved statues of rabbis with students, people praying and orthodox Jews playing violins. It was summer and I had finally come in from the cold.

Although the streets were surprisingly empty, I was encouraged by renovation work being done on the synagogue and the cemetery. As my experience in Eastern Europe had shown me, most Jewish communities I had visited were so poor they couldn’t afford to fix their facilities. Here, however, the Remu’h Synagogue was filled with scaffolding and workmen doing renovations and the Remu’h Cemetery right next door was busy with a small group of 20-somethings cleaning and repairing old gravestones. Cleaning couldn’t have been easy. The stones that remained intact had survived Nazi brutality only to fall victim to the ravages of acid rain. Instead of tossing crumbled stones, many larger pieces were plastered on a wall at the front of the cemetery to create a mural of death. To protect the markers from further decay, the group had placed small hoods over the tops of the stones to keep the rain from further eroding the lettering. In theory, putting metal visors over the top of the stones makes sense. The application is problematic because it makes the proud, ancient headstones look goofy. It robs them of their dignity. It was the graveyard equivalent of going into a hospice where people try to die with dignity and making every resident wear a pointy party hat. It’s just not done.

Still, it’s hard to argue with success and it showed the Jewish community was trying to keep up appearances.

“I just got to Krakow and I’m so excited,” I wrote a friend after my first visit to Kazimierz. “Not only are there traces of the old Jewish community [but] the current one is thriving! It’s enough to make me cry.”

My elation was short-lived.

Journalist that I am, I interviewed Henryk, one of the city’s oldest Jewish citizens, and heard the discouraging word: The city’s Jews aren’t thriving, they’re dying. Henryk estimated there were only 170 practicing Jews, all old. Once they’re gone, there won’t be anybody to replace them. They won’t have to worry about the neighborhood’s Jewish cultural institutions dying out, however, because Jews aren’t even running them anymore.

As difficult as it was to believe, not one of the waiters, waitresses, restaurant owners, booksellers, gallery managers, performers or organizers of the cultural center are Jewish. Judaism wasn’t a living, breathing thing in Krakow. Instead, Krakow was to Poland what Williamsburg is to colonial America, a remembrance. The only difference is that Krakow didn’t have people sporting period costumes to make them look like orthodox Jews. (Thank God.) It was a museum Judaism. Like the Museum of Extinct Peoples Hitler hoped to establish once he’d killed all of Europe’s Jews.

I don’t mean to belittle the efforts, though. They’ve done an amazingly good job of keeping the patient on life support as it staggers along, increasingly slowly, bringing the ground closer every day. I expect tourist dollars also provide some incentive, but you still have to have passion for the subject to do as good a job as they’ve done.

Still, it’s not live, it’s Memorex.

The news changed what had almost been tears of joy to heart-wrenching, gut-wracking sorrow.

After three days of wandering between Kazimierz and the old, Medieval city in the center of Krakow, I decided to day trip to a beautiful, bucolic suburb that made me think of the Midwestern US in the late 1800s. The kind of place that seemed so remote that nothing ever happened.

Its name is Oswiecim.

But most people know it as the home of Auschwitz where more than 2.5 million Jews were killed.

Riding through the agricultural outskirts of town more than 40 years later, it was hard for me to believe such horror could happen here. Of course, it’s still difficult to fathom that such barbarism could happen anywhere, but especially not on the outskirts of Oswiecim, a place that even today looks more likely to be associated with the best example of bucolic backwardness Poland has to offer than a shiny, super-efficient high-tech death factory.

It just doesn’t fit.

Like most of Poland, the land that surrounds Oswiecim is so pretty it defies description. It is where the country’s Montana-like land of the big sky meets the American Midwest with rich farmland and green hills stretching beyond the mind’s eye and into the imagination. If the world were flat and one of the edges was in Poland, the cliff would have to be at the end of a lettuce field right here. Things don’t die here, they grow.

If I had to choose any place where such horror would be likely, this wouldn’t be it. It would be some place where all hope is gone and is unlikely to return. Flint, Michigan; Detroit after dark; East St. Louis, Illinois; Liberty City, Miami; Compton or Watts in California. Of course, much of Germany was such a place after World War II, but now it was hard for me to believe this was ever a place where thousands of Polish political prisoners and Jews were deported and either gassed upon arrival or worked and fed so little they eventually died from exhaustion or were killed when they just couldn’t work any more.

The Auschwitz-Birkenau deathplex may have had more than 330 prison blocks, four huge gas chambers complete with crematoria and guard towers and barbed wire seemingly winding beyond the horizon, but the size of the crime was so unfathomable to me that the only thing I could get my mind around were little things. And even they weren’t little: Stacks of spectacles, mountains of hair, piles of suitcases with the names of victims brought the lesson home in a way none of the plaques or displays possibly could.

There were two tour guides who told stories that caused a catch in my throat, though. One said he was giving a tour through a room where thousands of suitcases were piled when a man in his group cried out in shock after seeing his own name on a bag from 40 years before. Another guide mentioned that the man who pulled the shit wagon had the best job in the camp because the stench kept Nazi guards from getting close enough to abuse him.

Not knowing my family history made the visit even more difficult for me because of the large numbers of lists of names throughout what was left of the camps. Each time I came across names of people who died during a particular day or incident I would read it with anxiety, excitement and fear. Anxiety and fear out of worry that I might see Wolkowitz on the list. Excitement for the same reason. I can’t say I wanted to see my family on the list but, at the same time, I wanted to see it somewhere. After all, if I see a family member’s name, I’d have something to work with. If not, then I still won’t know what happened. Surely, there must be somebody who’s still alive, maybe even in a hostel in the same city at the same time or halfway across the globe wondering the same thing at this exact moment.

In a way, I hoped if I must find their names on any of the plaques throughout the site that it be on a list of people who put up a fight rather than one of the prisoners who blindly obeyed. More than likely, however, the truth is somewhere in the mundane middle, that they were average working zdlubs like you and me, living quiet lives and overwhelmed by what they saw. I know I have a sense of inner strength that has allowed me to deal with adversity head on and a stubborn streak so wide that I can’t believe it just came from my mother’s side of the family (although her people are plenty stubborn). Sure, my grandfather was pig-headed and obstinate, but Ida Volkovitz, my fraternal grandmother was no slouch either. After all, my mother felt the only way to break her control of my dad was to move as far away from Pittsburgh as she possible. Which explains why I grew up in Fort Myers, Florida.

The last bus to Krakow may have been filled with people chattering, shivering and trying to get warm after a sudden cloud burst occurred while we were all standing outside waiting for a ride back. I sat alone, depressed and filled with sadness, wishing I had a friend to talk to.

My visit to Krakow wasn’t unrelentingly depressing, though. After all, it’s hard to be depressed in such a pretty city. I agreed with the assessment of the Warsaw artist who said, “Krakow, now there’s a city.”

As far as I can figure, the key difference between the two cities is luck, military strategy and being in the wrong place at the right time. The Nazis looted the city, but didn’t have enough time to do the damage they did in Warsaw. Apparently, they were about to blow up a castle, a cathedral and other major landmarks when a Russian sneak attack sent them packing. Krakow’s lucky break made it one of the few towns with an old city and ancient monuments still standing after the War. With more than 6,000 monuments and historic buildings, there were plenty of things for me to see and do when I wasn’t chasing ghosts.

Although I tried to visit most of the monuments, cathedrals and shops in the Old City, those aren’t what stand out in my memory, however. Instead, I remember the amusing little details I noticed as I wandered around the city’s Market Square (Europe’s largest medieval town square). There was the trumpeter in the tower of St. Mary’s Church who rung in the arrival of each new hour with a five-note blast that ends abruptly in mid-bar. According to legend, the shortened tune is played to this day in honor of a watchman who spotted invading Tartar forces and sounded an alarm, which was cut short when a Tartar’s arrow pierced his throat. (I prefer the alternative legend, which says the trumpeter’s blast stopped when a small girl offered flowers to the watchman. He was so touched by the gesture that he lost his breath and the note died.)

There was also the fun of strolling through the side streets and listening to performers playing tunes on a dizzying variety of instruments with a wide range of skill. My favorite group was made up of two 10 year-olds valiantly struggling to play recognizable tunes on key — any key — and failing miserably. Their rendition of “In the Mood” was so slow and hopelessly off-key that even the trumpet player winced while reaching for high notes. Their effort was so delightfully bad I added it to a street sounds tape I recorded for my younger sister. When she received the tape two weeks later and replayed it without knowing how cute the kids were, she complained, “Even from halfway around the world he still finds ways to torment me.”

My sister wasn’t alone in her complaint about being tormented. Just as I finished taping that day, I heard the familiar strains of a song that couldn’t have been more out of place unless it was someone playing “Hava Negila” in Iraq.

When I rounded a corner in the old city I realized the song was indeed “Guantanamera” and that the damn Andean band was still dogging me.

As bizarre as it sounds, the biggest thrill of my Krakow visit outside of the Jewish quarter was finding a place to stay in a college dorm with a laundry. A washer and dryer may not be such a big deal for most travelers, especially in America, New Zealand and Australia where there are Laundromats in abundance, but it was huge to me because I hadn’t even seen a washer since leaving Australia in March and had washed my clothes in bathroom sinks for four months. Not too surprisingly, washing filthy, sweat-soaked clothes without a machine never really gets out the dirt or smell (which may explain why backpacker districts are often on the edge of downtown areas in every city in the world). Consequently, I hadn’t thoroughly washed my jeans since that ugly incident in Latvia, I didn’t have enough warm clothes to take two days out to wash and dry my sweatshirt and my socks were so dirty, smelly and stiff I wouldn’t have been surprised if they had walked out on me. I don’t even want to talk about my underwear.

I stumbled across the final pick-me-up when I stopped in a stationery store to get a new travel journal. It wasn’t the best or even the biggest, but I couldn’t resist buying a journal book called “Globtrotter” because it was the perfect souvenir of a country that doesn’t know how to use vowels after all these years and all those extra lend-lease shipments from the IMF. I bought it gleefully and walked away laughing.

I didn’t get the last laugh, however. When I was writing in the journal a few months later, a kibbutz volunteer saw it and said,

“What the hell is a ‘globtroter?” The Poles had left off a “t,” too.

As the late-night train to Prague left Krakow, I pulled my Walkman out of my backpack, put in a cheap country music tape from the Kountry Piknik and lay back in bed. Until I heard THE song. It sounded so familiar I knew I’d heard it somewhere before. It took

me almost until the end of the song to realize that it was “Achey, Breaky Heart” In Polish.

An appropriate end to a heart-breaking visit.