Scenes from a Latvian Living Room and other Tales of Jewish Geography

I fall victim to the great TEFILLIN ambush of 1996.

“Now you can tell your friends you met a real live Communist!”

–Grandfather of a Jewish womanI met in Riga, Latvia.

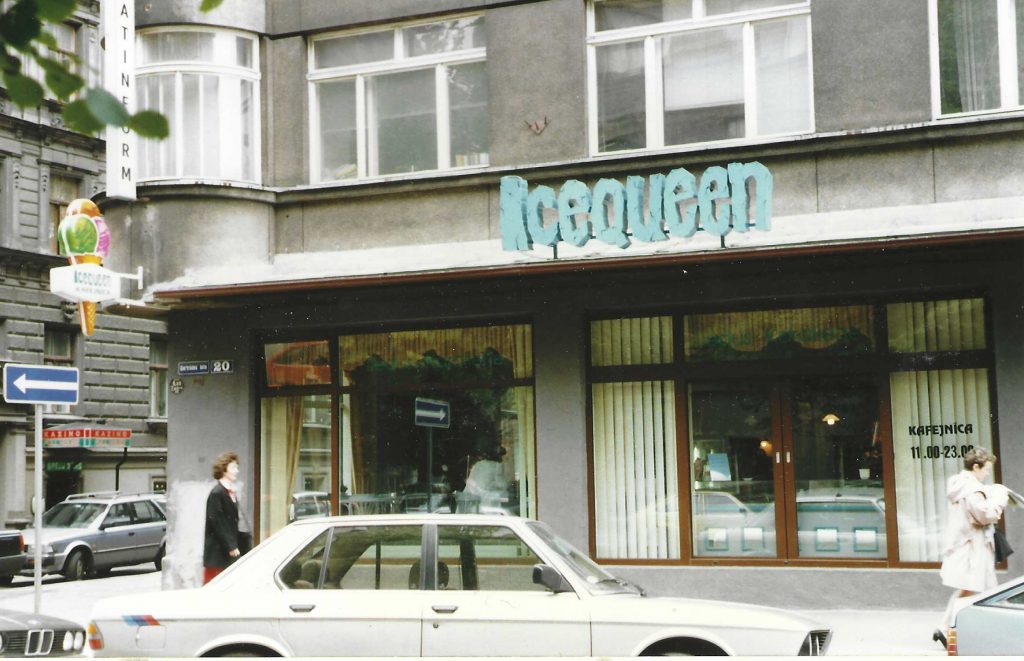

One of the things I like most about Riga, the Medieval capital of Latvia, are its smells. As soon as I roamed to the central part of old Riga I caught the most tantalizing aromas and followed them from restaurant to restaurant and bakery-to-bakery, searching for the source, but I couldn’t ever find it. So, I ate something in every restaurant and bakery along the way.

The smells were amazing. One minute it seemed to be the scent of chocolate. Then, a dash of cinnamon. Next, it was bread baking or meat cooking. Whatever it was, it was brilliant, but elusive. And it sure beat Indonesia’s sewage smell.

Yes, I could easily fall in love with Riga in the summer — the old buildings, the smells, the medieval architecture — except for one detail: the destruction of the ghetto.

I’m not talking about the first destruction of the city’s major Jewish neighborhood under the Nazis, though. That would have happened even if the Germans hadn’t been able to co-opt the Latvians. It was out of the control of the local populace (but that doesn’t excuse the city’s willingness to curry favor with the Nazis by treating the Jews even worse than the invading armies — a thought as horrifying as it is unthinkable). Instead, I’m referring to Riga’s allowing what was left of the ghetto, the old Jewish cemetery and other remnants of the city’s Jewish enclave to come down bit by bit with no effort to preserve it.

To my way of thinking, the ghetto is one of the most powerful reminders of what happened here and how easily the Latvians fell in line. Without it there is little actual physical evidence of what happened here. Sure, there are survivors, but they’re dying off and, besides, buildings outlast generations. Some people still claim the Holocaust never happened and their voices will grow louder once the last survivors die. It’s hard to refute something as concrete as bricks and mortar, however.

I’m not talking about the first destruction of the city’s major Jewish neighborhood under the Nazis, though. That would have happened even if the Germans hadn’t been able to co-opt the Latvians. It was out of the control of the local populace (but that doesn’t excuse the city’s willingness to curry favor with the Nazis by treating the Jews even worse than the invading armies — a thought as horrifying as it is unthinkable). Instead, I’m referring to Riga’s allowing what was left of the ghetto, the old Jewish cemetery and other remnants of the city’s Jewish enclave to come down bit by bit with no effort to preserve it.

To my way of thinking, the ghetto is one of the most powerful reminders of what happened here and how easily the Latvians fell in line. Without it there is little actual physical evidence of what happened here. Sure, there are survivors, but they’re dying off and, besides, buildings outlast generations. Some people still claim the Holocaust never happened and their voices will grow louder once the last survivors die. It’s hard to refute something as concrete as bricks and mortar, however.

I discovered the sad situation after arriving in the country’s capitol city, dropping my stuff at a college dorm where I had found a room and hit the town so I could walk the streets where my grandmother and her relatives may have walked and see the places they saw every day. It seemed to me that one of the best ways to do so was to go to the old Jewish areas and wander the ghetto.

Sadly, as LP points out, little remains. One of the few exceptions is a memorial on the site of an old synagogue on Gogola Lela. When the Nazis invaded the city on July 4, 1941, they rounded up the Jews, locked them in synagogues and burned the buildings to the ground. Since most of the houses of worship were wooden structures, most burned down to their foundations, leaving little trace. Since the Gogola Lela structure had a stone foundation, however, there are still traces of one of the city’s finest synagogues.

What little remained after the initial onslaught has been wiped away by the intervening years. The devastation of memory is so total I couldn’t even find some of the streets listed in LP as being the boundaries of the ghetto, and the old Jewish cemetery is now a park devoid of gravestones without so much as a simple plaque mentioning how the land had been used in years past.

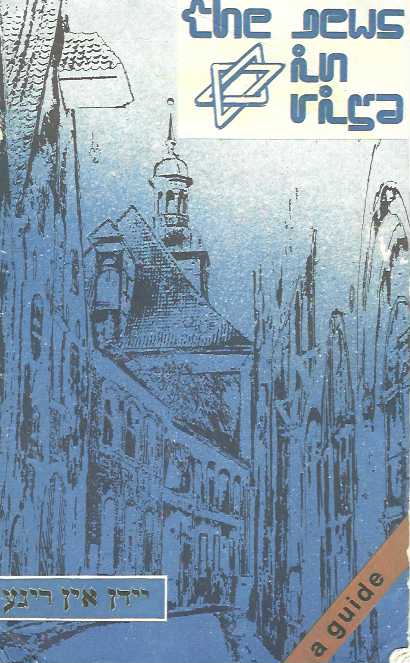

It was a miracle that I found the Jewish Cultural Center. If I hadn’t read an English language entertainment newspaper with a calendar item listing an exhibit on the Jews of Latvia, I might never have known it existed. The exhibition was small but good, filling two small rooms and a corridor with photos of the Jewish experience here. The first room concentrated on Riga up to the 1930’s, the second focused on the mistreatment of the Jews leading up to the Holocaust. As I walked through the displays and saw how Jews had been treated over the years, especially in the early 1930’s when their rights were increasingly curtailed, I asked myself how they couldn’t see it coming.

It’s funny how little things can make an unexpected difference. I was talking with the center’s art director in the lobby about the exhibit when I happened to mention that I was visiting Riga because I wanted to see where my grandmother lived before she ended up in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The mere mention of the town provoked a cry of excitement from a young woman who was in the foyer. Considering that she wasn’t wearing a Steelers or Pirates cap, her outburst puzzled me until she explained she would be leaving for Pittsburgh in a few weeks to attend business school at the University of Pittsburgh. So, we spent an hour exchanging information about Pennsylvania and I gave her the names of relatives near the university she could contact. In response, she offered to take me on a weekend tour of a nearby resort city. How could I say no?

In keeping with the focus on Judaism, I stopped by the city’s only prewar synagogue. (The only thing that saved this synagogue from destruction was its proximity to other residences and businesses. City officials genuinely feared they might not be able to control the fire.) While I was there, the rabbi invited me to dinner the following night.

Having nothing to do, I went to see “The Bird Cage” on its last night, but went to the wrong theater. I’m no Steven Segal fan, but I soon realized I didn’t have enough time to make it to the other theater. So, I either had to see “Executive Decision” with Segal and Kurt Russell or nothing. As it turned out, Segal dies in the first 20 minutes and it’s much better after that.

Once I left the theater, a strange thing happened. I had one of those odd moments when I was truly bowled over by where I was and what I had done. During the trip I never forgot what country I was visiting or what I hoped to see, it’s just that there were times when I marveled at the enormity of it. “I’m in fucking Riga man!” I felt like yelling as I walked out of the movie and asked myself how the hell it was that I had gotten there. Sure, I knew I had taken a train from St. Petersburg, but I was still mystified after years of talking about taking this trip that I’d finally gotten up off my butt and done it.

And it was good.

Before I left I knew traveling with ulcerative colitis wouldn’t be easy, but wasn’t going to let it slow me down. Sure I knew I’d be in strange places where I might not be able to find a bathroom if I desperately needed one. I also knew painful flare-ups could come without warning, forcing me to find a come on at a moment’s notice, forcing me to find a bathroom immediately or face the consequences, but I had to take the chance.

When I left the States, I had been healthy for several months and had been conscientiously taking my medicines. The problem with the disease is its unpredictability. A colitis patient can go years without symptoms, then flare up suddenly for a brief period. Alternatively, a sufferer can also suffer years of flare-ups and have them stop suddenly. Not only do doctors not know what causes the condition, they also don’t know what causes the disease to flare up or remain inactive at any given time.

The only thing I know for sure is that it’s not pleasant. At its best, it’s an inconvenience, forcing me to pay attention to my surroundings, know where a bathroom is at all times and limit what I eat when traveling. At its worst, it combines the pain of constipation with the urgency of diarrhea and produces almost arthritic pain in many of the body’s joints. It can also cause spasms in the sphincter, reducing my body’s ability to start the flow or even stop it once it’s started.

After six trouble-free months, it came back with the same vengeance you’d expect from a scorned lover who has discovered you’ve moved out and left no forwarding address, forcing it to spend six months trying to track you down. The disease was back, and it was pissed. (Perhaps it would be more appropriate to say it was in a shitty mood?) Instead of exerting its iunfluence with a series of power plays, however, the disease launched a subtle, sneak attack.

It was so humiliating that it’s difficult to write about.

I had just finished lunch and was headed back to my dorm room when I realized I needed to go. NOW. Since I was closer to where I was staying than the restaurant I had just left I decided to tough it out and hit the bathroom before disaster struck.

I chose….poorly.

I not only didn’t make it, but in my rush to get up the dorm stairs to a bathroom I suffered leakage. Shit rolled down my pantleg, but somehow I managed to keep it from dropping out of my jeans. It made an unholy mess.

Back in the States this is the type of situation where I would have immediately thrown my clothes into a washing machine, but I wasn’t at home, there weren’t any laundromats and these weren’t stains I could easily clean by washing my jeans in the sink. As a result, I had to endure the utter embarrassment of taking my pants to a dry cleaner and explaining the problem to someone who spoke English as a third language.

Oddly enough, I felt childish and mature at the same time. Given my lack of control, I wasn’t surprised to feel like a child. What pleased me, though, was how mature I felt because of my desire to deal with the problem quickly rather than tossing the jeans and avoiding the issue. While I didn’t have clothes to spare, I could have just purchased another pair even if they were expensive. Once I decided against walking away I felt I’d passed through an unmarked passageway on the road to being a grown up.

One of the disadvantages of responsiblity is it takes so much longer than irresponsibility. If I had just thrown them away I could have had a nice afternoon nap, and I really needed it. I was already tired when the incident occurred and it took me so long to clean up and walk to the cleaners that I only had a half hour nap before I had to leave. If I’d followed my old modus operandi, I would have had a good, long nap and woken refreshed. Instead, I was barely awake when I finally got to dinner.

I never thought I’d not be interested in a Jewish woman because she was too religious, but it happened in the rabbi’s apartment that night. The rabbi and his wife had three female college students staying with them while they worked at the Jewish summer school where he was principal. The girls may have been cute, but they were Chabadniks who had bought into Orthodox Judaism’s definition of women as second-class citizens who can’t lead prayers, be rabbis or be part of a minyan. I didn’t buy it and I couldn’t see how such educated women could, but they had.

While I was marveling at finding someone who was too religious for my taste, the rabbi and his charges were trying to get me more involved with Chabad. I was having a hard time biting my tongue to keep from saying that I hadn’t yet been in a Chabad House (other than in Bangkok) that I’d liked. My experience is that they’re loud places where undisciplined children run amok and women are second-class citizens.

The rabbi was also after me to put on tefillin and asked when I had done so last. For the uninitiated, it’s hard to explain what tefillin is. The process of putting on tefillin is a ritual observant Jews do as part of their morning prayers. First they take a funky, wooden box-like appurtenance with straps coming out of it and put it on their heads. Then they put another on their left arm and wind the leather straps coming out of it in symbolic patterns, but I don’t know whether the symbolism is social, historical or statistical or if I have to round to the nearest number. Once the person looks like a cross between a complete dork and Frankenstein’s monster with a too big bolt on the front of its head, he thanks God.

Far be it from me to belittle religion, but I think this is god’s idea of a practical joke. Every time I see a roomful of Jews wearing them I can’t help but think god is sitting somewhere in heaven laughing his ass off at our expense saying, “I still can’t believe they took that commandment seriously.”

I wasn’t avoiding putting on tefillin because I had an aversion to looking like a dork, though. I’ve been doing that for years. Instead, I avoided it because I didn’t know what I was doing. My religious training had included this lesson numerous times but I never got the hang of it. I knew the rabbi would be happy to help, but I didn’t want to be pushed into anything.

The rabbi’s brother cornered me at the synagogue earlier in the day and convinced me to do it. The rabbi was shocked when I showed my ignorance, but quickly said “this calls for a L’chayim.” Anyone who has ever seen “Fiddler on the Roof” knows the phrase is a toast that means “To Life!” To the rabbi’s thinking, however, it meant “Let’s drink more vodka” because that’s exactly what he wanted us to do when he found out about my reluctant journey into piety. When the rabbi discovered I’d put on tefillin the day before, he insisted on another shot of L’chayim. Since I already had plans for Saturday, he wanted to do another toast for my doing tefillin on Sunday, but I wouldn’t make such a promise. Having already poured a third vodka shot, he insisted we drink to something else, which I agreed to do, but refused to finish the whole thing because the vodka and the lack of sleep were catching up with me and I knew I’d end up face down in my dinner plate. While I trusted the rabbi and knew he wouldn’t roll me and leave me outside on the sidewalk, I wasn’t convinced that I wouldn’t wake up to find tefillin on my head, so I never finished the final drink and left around 1 a.m.

Having had so little sleep, it wasn’t easy to get up in time to meet the woman who agreed to show me around Saturday morning. Fortunately, she’d gone to a graduation party the night before and we agreed to meet at noon so we could get more sleep.

An afternoon trip to Jurmala, a Baltic Sea resort town where many Rigans escape for holidays, was a treat, but the return trip was even better because she asked if I wanted to see her family’s apartment. Although I hoped for an invitation, I didn’t expect it. Once she made the offer, I jumped at the chance to see how the locals live.

Her apartment complex is located on the train line halfway between Jurmala and Riga. From the outside, the building isn’t much to look at and blends in with the rest of the Soviet-era block style apartment buildings nearby. Inside, the building’s corridors are dark — because the light fixtures are either broken or haven’t seen a bulb in years — and many of the walls are spray-painted, making it look and feel like the inside of housing projects in New York and Chicago. Once we entered her apartment, though, I felt like I had stepped out of a run-down tenement in East St. Louis and into a small, nicely appointed family apartment in a middle class neighborhood in Kansas City. It wasn’t posh, but it was comfortable with narrow kitchen and a walk-in closet along the same wall as the front door. The first room was an anteroom running the width of the apartment. The next, the living room, also ran the apartment’s width with a sofa against the front wall and the back wall while bookshelves took up the entire left side wall. A big color television sat on a small table on the far right wall. A small hallway led to the remaining four rooms: her parent’s room, the room with the sink and shower, a water closet with a toilet and then there was Diana’s room.

To me, her door was the most interesting part. It had smoked glass from just above knob-level to just below the top of the doorframe, looking much like a door leading into an office in an old detective movie. The only thing missing was having a name painted on the glass like “regnaD kciN.”

]Just as I got ready to leave her family invited me to dinner. The meal included potato soup, chicken, fried fish, macaroni, mushroom salad, wine, beer, Sprite and much chocolate. The food was excellent. In fact, I can only had one bad dish when I was in Riga and that was because I didn’t know what it was.

The only problem during the meal was the language barrier. I don’t speak Russian, German or Yiddish and her family doesn’t speak English so she ended up interpreting. Her father was a big bear of a man who had a small facial tic or a stutter and made up for it by talking very fast. Her mom, also quite nice, understood more English than she spoke and was outgoing and friendly. I got the impression she would have liked to fix me up with her daughter if only Diana weren’t already dating someone. Her grandfather was my favorite family member, however, because he was big, had a gruff voice like a grandparent should and was very funny.

“Now you can tell your friends in the States you’ve met a real live Communist,” he kept telling me (in Latvian).

Dessert included small chocolate pastries that tasted the way Summit candy bars tasted years ago. There were also fancy boxed chocolates, which were an adventure to eat because the bottom of each one stuck to the candy tray. After we all laughed at the stubborn sweets, I told the family of my love for a pastry I’d discovered in town: a round roll filled with poppy seeds and covered with chocolate frosting.

Although I don’t remember the exact spelling, Diana told me they were called “boulski (pronounced “bull-shki”) shmeckems. Just hearing the name made me bust out laughing because it sounded more like a threat than a pastry. I could see a parent telling a child who hadn’t cleaned his plate being told this. Worse, I could hear a mother quieting two squabbling kids by saying, “Hey, if you don’t stop, buolshki schmeckem, right here and now! Is that what you want?”

When dinner ended Diana and her mother took turns on the phone while the men watched a game show called “Intellectual Roulette” in which corporate smart guys play on teams where they answer hard questions and solve difficult problems. Granted, the problems may have been complex, but I couldn’t get over one guy who mopped his brow while searching for the solution. After all, it wasn’t brain surgery and the contestants were only playing for rubles. It wasn’t like they were playing for real money.

I finally left around 10, even though I had tried to leave earlier so Diana would have time to visit her boyfriend. She didn’t mind, though, and everyone seemed sorry to see me go including her grandfather, who beckoned me to him so he could impart final words of wisdom.

“Eh, now you can tell your friends you’ve met a real live Communist,” he said.

After having walked the streets my grandmother walked, ambled through the ghetto and seen all of the big landmarks of Jewish life in Riga, it seemed a good time to look at the Jewish way of death by visiting Smerli, the New Jewish Cemetery. I knew the cemetery hadn’t opened until the 1920’s, but I hoped I might stumble across a Rubenstein (my grandmother’s maiden name) even though my grandmother had emigrated to the States long before then. Unfortunately, I couldn’t find one.

It was a busy day at Smerli. Not only were there people waiting for a funeral, there were more than a hundred people visiting loved ones, lovingly tending their graves, clipping weeds, cleaning trash and reducing overgrowth. Although people do the same thing in the States, I’d never seen that many people at a Jewish graveyard when there wasn’t a burial. Of course, the last few times I’d gone to a graveyard to visit my father’s I’d done so mid-week, not on Sunday, but I don’t think there was ever this level of foot traffic at the Jewish cemetery in Fort Myers.

Even without crowds, the cemetery was far different from what I’d seen back home, especially the headstones. At some Jewish cemeteries in the U.S. I’d seen stones sporting buttons with pictures of the deceased, but that had become a rarity at graveyards because vandals used them for target practice. That wasn’t a problem here because Latvians had found a solution. Instead of adding a picture to the stone, they made a picture part of the stone. I don’t know how, but it looked like they’d transferred photos onto granite. The result, especially in the case of husbands and wives, was the disconcerting effect of having the couple stare at you every time you visit.

Then there are the stones with heads sticking out. I don’t know how to describe it other than to say it appears that a sculptured head had been artfully — though not altogether tastefully — attached to the top of the grave stone.

The only other grave of interest was at the far end of the cemetery. I had never heard of a mass grave in a cemetery before because the Nazis typically did mass killings in forests, on the edges of town or, in Latvia, on beaches. They simply dug a large trench, lined everyone up, mowed them down and covered the hole without leaving a marker. So, I was curious to see how Smerli marked the spot.

Like the pit it covered, the grave ran the length of the far edge of the cemetery and was outlined by a rock border. The result looked like two extremely long graves with a headstone and plaque at the foot of the grave. It’s still difficult for me to say which was more disturbing: a marked mass grave or headstones with the faces of couples looking back at me as I walked away.

I wasn’t expecting the ambush when I walked into the principal’s office at the Jewish Day School, but I should have. After all, it was run by the rabbi I had been dodging since the week before. I’m sure a visiting official from the Jerusalem office of the Jewish Agency wasn’t expecting the sneak attack, either. He had just been kind enough to walk me to the new school and the rabbi hit him as soon as he walked in the door.

And made him put on tefillin.

For Yossi, a man with a Gene Wilderish face, it was the last in a series of surprises on an otherwise uneventful day. For starters, he never expected an American Jew to show up on his office doorstep asking about summer camps and summer schools for Jewish kids. After all, Riga not only isn’t a backpacker destination, it’s not a place that sees a lot of Americans. When he called the Israeli embassy for information and was told there were no summer programs for children, he was surprised that I insisted there was a program. And he was even more shocked when he called the rabbi’s wife and learned I was right.

He was so stunned he wanted to see it himself.

The school is in an area within the ghetto walls. In fact, it had been a Soviet run school from the late 1940s until the 1990s. The school was one of many buildings returned to the Jewish community in the years since the fall of Communism and the re-establishment of Latvia as an independent country.

Even though many buildings originally owned by the Jewish community before World War II were finally being returned to the community in the mid and late 1990’s, many remained closed because the small community didn’t have enough money to repair or maintain them. The school, for example, had only opened within the last year.

The rabbi was happy to show us around once he got the pesky tefillin problem out of the way. The building is an old two-story brick structure that looks like any big city elementary school back in U.S. Wide stairways for kids to navigate between classes, classroom-lined halls, a playground out back and an auditorium where kids gathered to attend assemblies and make noise. The only difference was a Soviet-style sleep room with beds in the basement so kids could sleep at school.

Midway through the tour, the rabbi offered us lunch, which was better than anything I’d ever had in an American elementary school: pitas, soup, herring (which I liked even though I’d always hated it before) and amazingly good chicken. The rabbi was called away in the middle, leaving us to fend for ourselves.

The unexpected sign of life in the city’s Jewish community encouraged Yossi, even if only briefly. With good reason. After six months in Riga, he’d gotten a feel for the health of the city’s Jewish community, and it wasn’t good. The demise of the Soviet system had given way to grinding poverty for the entire country because Latvia had few industries of its own and relied heavily on Russia for support. Not only were Jews not immune to those problems, they also had issues of their own because they were also persecuted under the Communist system, even if the abuse wasn’t as bad as that of the Nazis. As a result, many people who’d grown up being attacked for their religion knew little about it, and most were so gun shy about the problem that had attracted so much hatred they wanted to stay as far away from it as they could — even if freedom of religion was an option.

Ironically, in the years since Communism’s demise Latvians were so happy to be able to speak their own language again and so hated Russians that Jews were more popular than Russians, Yossi said. It was a sentiment I heard again and again from people in the community. Despite their suddenly elevated status, Yossi said, many happily left Latvia for Israel, the U.S. or anywhere they could go via Operation Exodus, the international Jewish community’s on-going effort to resettle victims of anti-Semitic persecution from former Soviet countries. While the trend wasn’t surprising, Yossi said he was shocked by another development he’d seen. Many people who weren’t Jewish claimed to be just so they could escape the economic difficulties they were facing at home.

“There’s something sad about wanting to leave your country that badly,” he said.

After a week, I’d heard enough sad stories and I was so tired of hearing the a song called “The Macarena” each time I visited the market I decided it was time to get as far away from the sad story of the country’s Jews as I possibly could.

So I went to Segulda, the heart of Latvia’s castle country.